Stuck in the Middle Of a Lean Leap

This is Part I of a two part series

Robert P. Thames, FACHE, FHFMA, President and CEO, Northern Arizona Healthcare

“Everything looks like failure in the middle.” – Rosabeth Moss Kanter

SUMMARY: All senior leader teams get stuck on their improvement journey. Examination of common stuck points for senior leader teams on their improvement journey provides insights into what works and what doesn’t. An improvement evolution framework is offered as a ‘GPS’ tool to aid leaders in building and strengthening their improvement “flywheel” for sustainable change.

Drawing on the latest thinking of experts in many fields and the latest doing of practitioners in diverse healthcare settings, the author reveals fundamental changes in how senior leaders execute the fundamentals of improvement. Many express dismay at the 15-20 year “spread” timeframe for a clinical best practice that is considered to be evidence-based medicine. However, we might be similarly chagrined by the spread of evidence-based management methodologies for organizational improvement.

INTRODUCTION:

In our value-based competition age, every organization is on a diligent performance improvement journey. With information on best practices[i] considerably more accessible and available than ever before, why are some organizations much further along their journey than others? While all organizations get stuck or side-tracked at times, why are some able to get un-stuck quicker and resume their progress?

In their seminal book Lean Thinking, Womack and James refer to the movement from lean thinking to action as a “lean leap.” However, while the term leap suggests getting over a chasm in a single bound, practitioners inevitably experience an unending array of challenges, fits, potholes, eddies, curves and obstacles. Often perceived as resistance, all of this feedback is information to an already information-overloaded senior leader team. Each piece of feedback is a test of the senior leader team’s commitment to its improvement path.

Finding reasons not to do something is always easier, especially reasons for not continuing on a course of more change. The temptations to “appease the natives,” or otherwise (temporarily) relieve or distract anxieties and abandon the current course of improvement are constant. In addition, lag time between starting a large-scale change and the observable results contributes to doubt that the change caused a positive effect (and instead may be mis-attributed to negative environmental factors) and fear-driven emotional communication. This leads to confusion and diffusion of commitment.

Is it any wonder that it is easy for a senior leadership team (SLT) to get stuck?

PART I: COMMON STUCK POINTS – AND HOW TO BREAK THEM

“Obstacles are those frightful things you see when you take your eyes off your goal.” – Henry Ford

Five common “stuck points” encountered by executives are described below.

Stuck Point 1: The frog in boiling water – are you hot enough to change?

The SLT is staring at a $20M budget gap. Again. There are no more rabbits to be pulled out of the hat. “We have scoured everything.” Tension, anxiety and frustration are palpable. A cloud of ‘here-we-go-again’ numbing fatigue hangs over them. There is a vague recognition that we are in an unhealthy pattern; the cycle must be broken, but how? And how confident is the team that a different approach will work better?

SLTs usually consist of smart, successful, hard-working and well-intended professionals. Yet our conditioning, based on what has worked for us in the past, can be a barrier for dealing with current challenges. Why? Because doing more of what we have done, faster, is a natural, reflexive human response. Tim Gallwey, author of “The Inner Game” series, refers to this habitual, default mode as “performance momentum.” He relates the habit to a ‘Maserati without brakes,’ noting that when driving a car, the ability to stop is as important as the ability to go.

How do we operate? Improve?

When a SLT is asked, ‘how do you improve?’ the responses often fall into one of three categories: 1) ‘more of what we’ve been doing, only faster’ (we just need more time), 2) too many explanations (wide variation), or 3) ‘too long’ of an explanation (lack of clarity). Confronting the question ‘how do we improve organizational performance’ usually reveals an approach of generating an array of micro-initiatives and improvement efforts, suggesting that more is better. Nearly all may be good ideas; some may even get implemented.

If pursued long or deep enough, a candid SLT conversation on ‘how do we improve’ often leads to the conclusion that the current approach won’t get us what or where we need to be by when we need it, i.e., our current approach is not sustainable. But what prompts calling that “time out”?

Courage and leadership

“I was tired of getting beat up,” said Elaine Couture, CEO of $900 million Providence Sacred Heart and Holy Family Hospitals in Spokane, Washington. A combination of state Medicaid cuts and a physician group acquisition by a competitor resulted in a $60 million gap. This was the gap that remained AFTER three different consulting firms did their slashing and recommending. “We were right back where we were,” said Couture. “I wanted to build my team’s confidence and enable our team to learn to fish. We have to own it.” She wanted an approach that works through her team, not for them or to them. Couture persuaded her system to engage a firm with the desired coaching philosophy and approach to help her team implement sustainable evidence-based improvement methodologies. After two 100-day Workouts[ii], the gap was closed. “Our team much prefers this approach and it shows in their confidence and energy,” said Couture.

Lisa Schilling, Vice President for Performance Improvement at Kaiser Permanente (KP), Oakland, California, delineates three phases of evolution: initiation, expansion and maturation. “There are stuck points in each phase,” she notes. In the initiation phase, a KP area SLT grapples with this “How do we operate?” question. It may start with a search for a methodology to adopt. It typically concludes with recognition that the particular approach is less important than trying something and adapting with it. “More than one methodology will get you there,” says Schilling. What is important is for the local SLT to exercise choice in which disciplined methodology they employ and that they are united in commitment to it. “A single view of ‘Big Dots’ and ‘truth to selves’” regarding performance was needed. “We were best-in-class, but not in everything,” said Schilling.

When executives identify their performance momentum trap and make the courageous effort to call a time out from their current, often unconscious approach to operating, they gain valuable insight and re-introduce purpose and choice. In the words of Will Rogers, “If you find that you are in a hole, stop digging.”

Stuck point 2: Beyond projects

Confronting the question ‘how should we improve,’ leads to a SLT debate and, often, paralysis. Why? Because any approach different from the default mode requires personal change from senior leaders. Besides, we are busy. Why take time from doing what I already know how to do? Just let me do it.

How should we improve?

Humans, even executives, don’t adopt or adapt at the same time. And some never do, as Peter Gosline, former CEO of Monadnock Community Hospital, and the largest critical access hospital in New Hampshire, discovered. Lack of executive level buy-in to a new improvement approach took the form of “passive resistance,” e.g., not showing up for key meetings or other undermining behavior visible to other managers. After coaching efforts produced little progress, Gosline noted that a couple of executives recognized their poor fit and left the organization. “Then we made great strides,” said Gosline. He then worked to assure executive roles and responsibilities are integrated into Monadnock’s new improvement approach, including assigning a different senior leader to lead each 100-day Workout, a key structure in Monadnock’s change model. Gosline’s team then worked to better wire the desired senior leader behaviors and expectations into the evaluation, selection and promotion systems.

“Leadership buy-in at the top is first,” says Donna Cooper, President of Dreyer Medical Clinic, a 210-provider (160+ physicians), 1200 employee medical group practice with eleven sites in the Fox Valley communities (west suburban Chicago) affiliated with Advocate Health Care. Dreyer started its lean journey five years ago, after retirement of a President. Cooper used a firm to jump-start her team’s journey and, after some big initial wins using lean in the first few years, they hit a stuck point.

“Leadership issues derailed us,” said Cooper. It became clear to Cooper that not every executive possessed the emotional intelligence and/or commitment required to make the personal transformation required for their journey. “All stuck points are leadership related,” notes Cooper.

“Over time the entire leadership has changed,” said Cooper. Some chose to move on in a natural attrition process; some were redirected; this included physician leadership re-alignment as well. Cooper used an organization redesign, multi-day retreats twice per year and visioning events with her team to assure cohesion and alignment. Then “we could move 100 times quicker,” said Cooper.

Schilling also emphasizes the import of leadership buy-in and “truth to selves” about performance. “It started with our CEO.” In 2006, George Halvorson convened Kaiser Permanente (KP)’s senior executives to clarify the challenge ahead and demonstrate the will to adopt the long view on improvement with an upfront two year investment and capital. The beginning is “really hard,” said Schilling. “The first year is very slow because a coalition has to form and build momentum. We needed to convince ourselves that we needed capability for improvement.” An Improvement Institute was initiated and focused training on two sites in the first year. Within five years, over 1,000 improvement advisors had been trained. Kaiser’s CMS scores are consistently among the top quartile; five of the nine health plans that Medicare gave its highest Five Star rating (best in care and service) to last year were KP regions; and KP’s cost trend was below its competitors.

The importance and the challenge to assure that all senior leaders are on-board with such a fundamental issue – how should we improve? – cannot be overstated. The top success factor in implementing such major change is unified CEO and executive team support[iii]. It is easy to tell when SLTs have addressed and resolved the “How do we improve?” question together. Their answers are concise, consistent, and confident. And they better match their response to ‘how should we improve?’ They can describe their “flywheel [iv]” because of their in depth understanding of how it is integrated throughout, and how it moves, the organization’s performance.

Stuck point 3: Beyond analysis: shifting culture from “heels to toes”

The intent is to assure that “1200 people are making improvements every day, not just management,” said Cooper. At Dreyer, standard problem solving using A3s, a highly structured communication process, awareness and transparency facilitate the desired culture change. Standard leader work is now piloted in four locations for team leads. This means Dreyer’s front line supervisors spend 50% of their time devoted to leadership activities doing standardized practices.

At KP, to standardize is to “Kaiser-ize.” An A3 at Kaiser is called a “two-pager.” Schilling explains that KP aims to constantly learn what works, what doesn’t and to create generic methods, i.e., “not call it anything” but to ‘de-identify’ a particular method.

SLTs discover that finding opportunities to improve is not a problem; execution on the significant few is the challenge. Couture confirms that there is no shortage of both ideas and distractions to implementing them. She emphasizes the importance of assuring the accountability to get the outcome, not just focusing on the process for the process’s sake.

When author the was COO of 767-bed St. Anthony’s Medical Center, St. Louis, SAMC’s overall efficiency compared favorably with others and we had been stuck in a debate of the validity of various benchmarks or in further analysis on why we were different or already efficient. The collapse of the economy in late 2008 spurred our team to adopt a different improvement model to speed up our execution. “Improvement requires change, and all change is personal,” was my lesson. WE – I, our SLT – needed to change. Components of the approach, implemented with the assistance of an external coach, included establishing an expectation for all managers of at least two changes per manager per month, using a tool to measure and make transparent our rate of improvement, and rapid cycle testing. Our SAMC team changed processes to pull out $25 million in waste, resulting in a bonus for all staff in a year when many other hospitals had layoffs. A culture of accountability, where speed to execution is prized, and a disciplined cadence of accountability were antidotes to paralyzing analysis and “below the line[v]” behavior and excuses.

Stuck point 4: Focus of Time: Assuring it is on your organization’s side

A leader’s only currency is his/her time. How do we invest, and re-invest, it?

High leverage focus area prioritization

Dreyer’s strategic deployment and prioritization process involved determining what success looked like and what is needed to get there. Dreyer’s SLT listed every single project to discern alignment. Then they delineated the daily work, parking lot or action items. They learned that they did not have a verify step so they established a visual management system which includes red/yellow/green indicators for key initiatives. Expressing her confidence in the Dreyer way, Cooper says, “Now I don’t even think twice about a metric.” Patient satisfaction is near the top decile and continues to increase; physician satisfaction has been at 98% three years in a row.

James Porter, M.D., Vice President and CMO of Evansville, IN Deaconess Health System ($600 million, 500 beds, 89,000 ED visits) noted that Deaconess applies the discipline of a matrix with key criteria to arrive at a point value for prioritizing and scoping projects.

ROI was a key issue for Dr. Porter as Deaconess started its lean journey in the late ‘90s with an engineering management orientation and a “distributive model” of deploying technical resources: selected managers were trained as green belts but still maintained their full time manager responsibilities. While Deaconess had some incremental successes, their SLT believed they were not achieving as much as they could as soon as they could. When the Deaconess SLT stepped back and examined the obstacles to next level performance, they decided an investment of seven full time black belts would get them further, faster. “The flood gates opened on projects,” said Porter. The training and experience also became a recognized catalyst for leadership development and succession potential.

Dr. Porter noted that “Each black belt has two-to-four projects at once. In year one we set a ROI target of 200%; in year two we changed our ROI target to 400%.” After a few years, the Deaconess SLT took another “step back.” We were doing good projects, but our SLT did not feel the progress on strategic level measures.” The SLT decided to adopt the 100-day Workout approach to focus on improving CMS measures. Encouraged by the improvements in CMS scores from this Workout, Deaconess has used the 100-day Work Out deployment system to pull out waste and to better match staffing to demand using the In-Quality Staffing method.

Gosline’s Monadnock team identified and documented over 1200+ improvement ideas over three years. He likens the “too many ideas” challenge to “accumulating emails.” Without a continued, systematic way of prioritizing existing and new ideas, “the improvement effort will weaken, the team will feel overwhelmed, people won’t take it seriously and accountability will suffer,” says Gosline.

Ironically, identification of more ideas can distract time and energy from implementing the ideas already identified. Identifying changes that would, in theory, result in an improvement is easier and cleaner than focusing on the messy business of actually testing, tweaking, collaborating and implementing them. However, continually a) identifying the vital few (ideas, projects), b) having the confidence that these are truly the top priority and c) having the conviction that we can and will get them done requires a disciplined prioritization and execution process aligned with corporate goals.

Stuck point 5: Unstuck capability: how will you know? And how quickly will you move on?

Depending on where they are on their improvement journey, leaders identified different stuck points with which they are currently grappling. As the CEO leading the transformational change in any, but especially a smaller, organization, Gosline shared the personal challenge of self-motivation. He noted, “There is a need to continually re-charge the batteries on this; it would be easy to “let go.” He recognizes that the CEO must keep pushing at least until sustainable “pull” is generated in the organization to help turn the flywheel.

Learning from others was fundamental to KP’s approach. Schilling’s team visited other healthcare improvement leaders and worked with Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) on an improvement framework. Beyond healthcare, Schilling’s team gained valuable insights on how and where to deploy Master Black Belts from Hewlett Packard (HP) and the value of using an “outside provocateur” from IBM. “Having an external eye and ‘hiring the mentors’” help recognize when we were stuck and in getting unstuck, notes Schilling. KP adopted a “learn, apply, share” philosophy. KP’s current stuck points (at the time of this interview) involve 1) knowing exactly how far to take lean in its application and 2) how best to integrate innovation and improvement. KP is testing the first with pilots in two area medical centers. An example of how KP is exploring the second question is the establishment of an Innovation Space called the Garfield Center. The Center was co-founded by KP’s Facilities and I.T. groups and enables testing of process re-design.

[i] Best practices here refer to those evidence-based processes and methods related to how to improve (improvement capability) versus prescriptions of what to do (a specific improvement, e.g., a specific clinical practice guideline).

[ii] GE is credited with pioneering the Workout change model, aka business deployment system.

[iii] Caldwell, Butler & Poston. 2009. Lean-Six Sigma for Healthcare: A Senior Leader Guide to Improving Cost & Throughput, 2d ed., Milwaukee: ASQ Quality Press.

[iv] The term ‘flywheel,’ from Michael Collins’ book Good to Great, refers to the organization’s operating model and improvement approach that progressively propels performance in a momentum-building and accelerating fashion.

[v] Collins, Roger and Craig Hickman. 2004. The Oz Principle: Getting Results through Individual and Organizational Accountability, NY: Penguin Group.

PART II: STAGES OF EVOLUTION – AND HOW TO MIGRATE

“You are here” and the Gretzky factor[i]

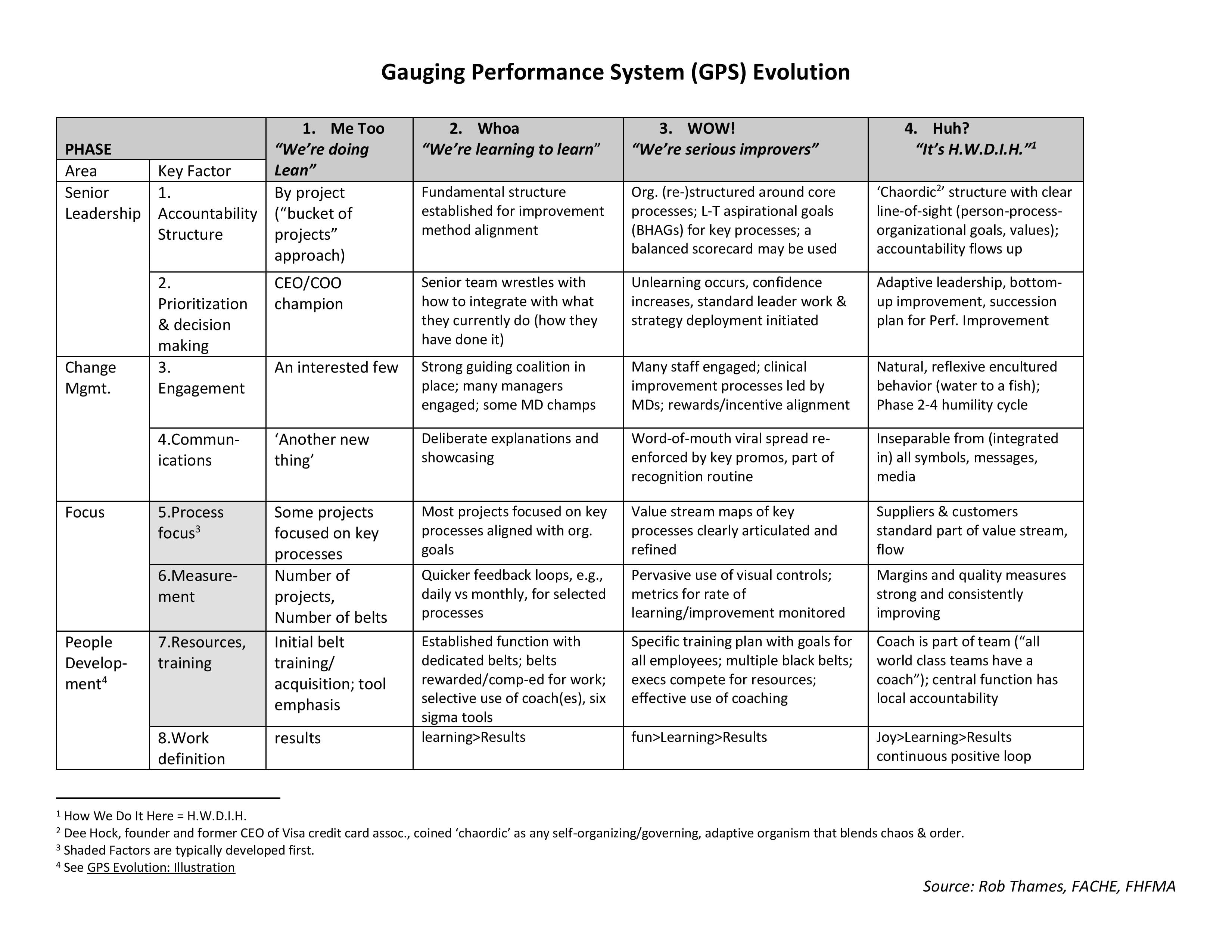

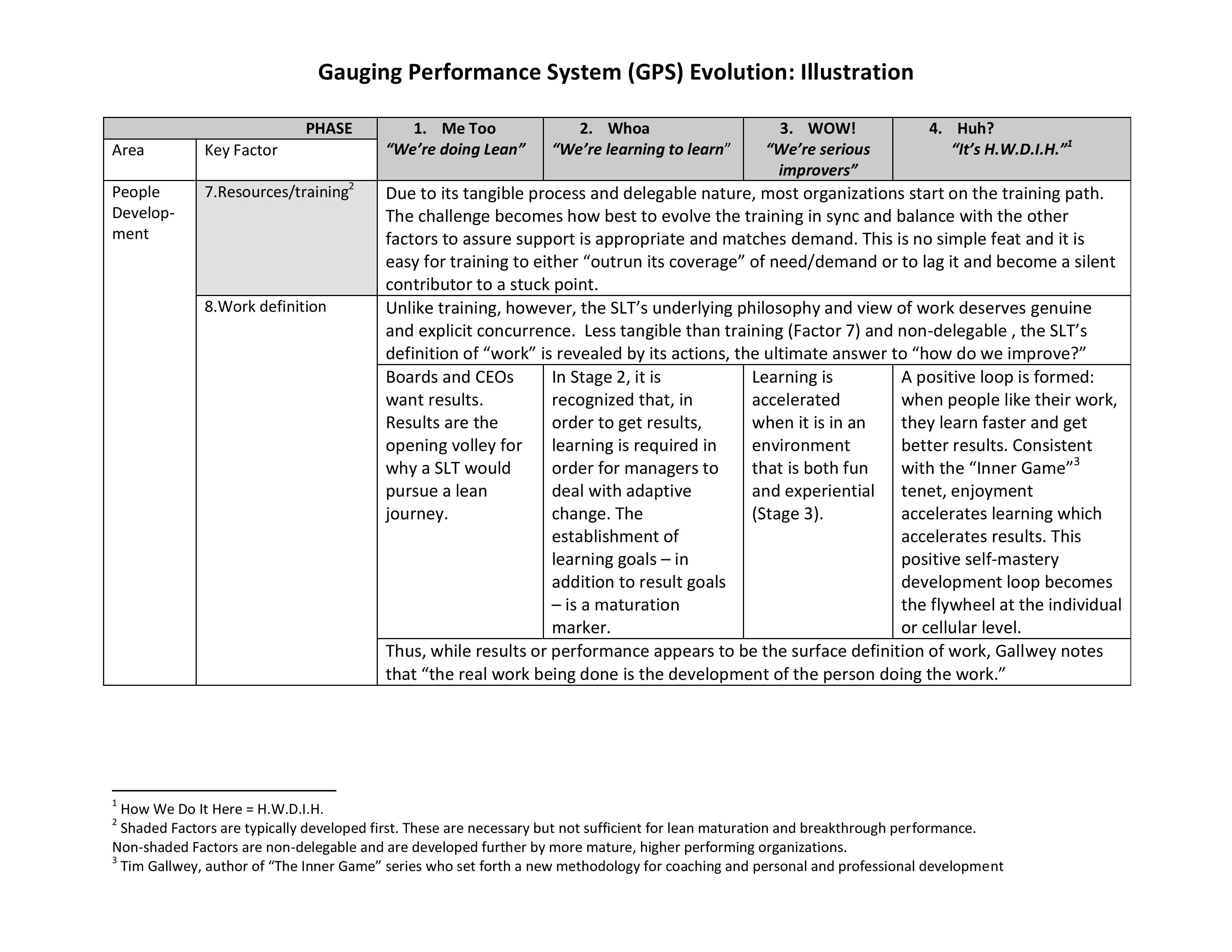

To assist in gaining perspective on ‘where are we now?’ in the context of an organization’s improvement or lean journey, a framework is offered as a combination GPS – Gauging (your) Performance System – and compass (‘where is true north?’) tool; see tables: Gauging Performance System (GPS) Evolution and GPS Illustration. Four stages of improvement evolution are delineated below.

Stage 1: Me Too

An initial step on the improvement journey is often marked by training of some staff in various tools. Because we have some tools, training and projects, the feeling is that “We are doing lean.” A few may be committed to it, but many/most are still in the ‘wait and see’ camp. Wide variation among senior leaders is common. These first steps are the easiest.

Stage 2: Whoa

In this next stage, acknowledgement and growing awareness that there is much more to this path and an early sense of greater potential is realized. The desire to tap that potential leads to a deeper, more serious commitment. However, leaders begin to learn that true personal change is required; it is not for everyone. The SLT needs to do things differently. There is an appreciation that now “We’re learning to learn” and perhaps that “We have only just begun.” This is steep, uphill work.

Stage 3: WOW!

At this point, an established discipline, reflected in a cadence, and significant, undisputed evidence of progress becomes self-perpetuating and motivating. The realization that “Hey, this really works” is followed by recognition that “We are serious improvers.” The earlier variation among the senior leader team significantly reduces as a natural selection process evolves. Many/most mid-managers are engaged. The SLT feels that it flirts with, or is frequently in, a ‘zone’ or what is described as “flow[ii].” This sense of being in full stride is engaging – exciting in a focused yet calm way.

Stage 4: Huh?

The most advanced stage is marked by a natural, sustainable rhythm that is perceived internally as simply “How we do it here.” For staff, the environment is like water to fish: most staff are hardly aware of the infrastructure to support the improvement; they reflexively do things this way because their behavior has been deliberately encultured. Leadership is characterized as adaptive[iii] and the accountability current flows up[iv]. The scope of efforts involves and engages patients, families and suppliers on a regular basis. Leaders have the humility to understand that some of their SLT, including themselves, and at least parts of their organization will variously cycle back and through stages three and even two. Staff and managers often self-correct; if not, leaders identify this behavior and have the ability to coach or otherwise address it appropriately.

Along with the stages of improvement evolution, eight factors examine different facets of the organization’s improvement maturation in four categories: Senior Leadership, Change Management, Focus, and People Development (see tables).

UNSTUCK CONCLUSION:

Organizations that begin a lean/improvement initiative more often than not first develop their Process Focus, Measurement and Resources/training (Factors 5-7). Emphasis is on tools, analysis and discovery. Many get stuck here and do not adequately address the first four factors. However, evidence suggests that what distinguishes quantum improvers from non-starters are an Accountable Change Model, a high level prioritization process, and a “speed to execution” culture of accountability inherent in the Leadership and Change Management categories (Factors 1-4)[v]. These areas emphasize implementation and dealing with resistance to change. This is consistent with Schilling’s assertion that a common stuck point is when local area leaders do not understand or embrace three things: 1) true leader alignment and prioritization, 2) the need to develop the capacity to improve, and 3) capability to execute using ‘rapid iteration cycles’.

A SLT’s discovery that striking the right balance between achieving performance and developing the capability to perform is critical to sustainability of results. The rate at which such discoveries are collectively made determines how long a SLT remains stuck.

What else can a senior leader team do to develop “unstuck capability?” A starter list includes:

- Anticipate common stuck points – maintain a healthy paranoia and periodically identify ‘we are here’ using the GPS tool

- Encourage courage – support calling a “the-King-has-no-clothes” time out to gain perspective; use an outside view and be coachable. Take the long view.

- Unify leadership commitment – expect personal change and SLT ownership of non-delegable factors. Warning: if this isn’t hard, you are not doing it.

- Learn from others – Be curious and practice humility. “It takes a wise man to learn from his mistakes and an even wiser man to learn from others’ mistakes” – Zen proverb

The changes required for improvement today are increasingly immune to past approaches. Greater senior leader team emphasis on learning to unlearn, getting comfortable being uncomfortable (leading without answers vs. ‘never in doubt’), and self-organizing (organic chaos vs. mechanistic order) is advised. The inconvenient truth is that such emphases are counter-intuitive, often counter-cultural, and require personal change. Which is why ‘unstuck capability’ is required for organizational improvement.

[i] Best practices here refer to those evidence-based processes and methods related to how to improve (improvement capability) versus prescriptions of what to do (a specific improvement, e.g., a specific clinical practice guideline).

[ii] GE is credited with pioneering the Workout change model, aka business deployment system.

[iii] Caldwell, Butler & Poston. 2009. Lean-Six Sigma for Healthcare: A Senior Leader Guide to Improving Cost & Throughput, 2d ed., Milwaukee: ASQ Quality Press.

[iv] The term ‘flywheel,’ from Michael Collins’ book Good to Great, refers to the organization’s operating model and improvement approach that progressively propels performance in a momentum-building and accelerating fashion.

[v] Collins, Roger and Craig Hickman. 2004. The Oz Principle: Getting Results through Individual and Organizational Accountability, NY: Penguin Group.

[vi] Hockey great Wayne Gretzky is credited with the notion: “Most players go to where the puck is; I go to where the puck is going.”

[vii] Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly 1990, Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience, New York, Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc.

[viii] Heifitz, Ronald, 1994, Leading without Easy Answers, Cambridge, Belknap/Harvard University Press

When dealing with “technical change,” where the problem is clearly defined and the solution is relatively straight forward, the traditional approach may be sufficient. However, because we are dealing with increasingly more “adaptive change,” where the problems are not clearly defined and new learning is required to address them, a different leadership approach is needed.

[ix] Connors, R. and Smith, T., 2011, Change the Culture, Change the Game, New York, Penguin Group, Inc.

[x] Caldwell, Butler & Poston, “Cost Reduction in Health Systems: Lessons from an Analysis of $200 Million Saved by Top-Performing Organizations,” Frontiers of Health Services Management 27:2

Robert P. Thames is a progressive healthcare industry leader with over 25 years of strong results in both operations and consulting within matrixed, multi-site/multi-function environments. Excels in strategy execution, physician partnerships, care system operations, performance acceleration, and managed care.

Passion for leading complex healthcare organizational change and helping leadership team accelerate pursuit of operational excellence and world class performance.