Continuous Improvement Capability: Has the training worked?

CONTENT PARTNER CONTRIBUTION

CONTENT PARTNER CONTRIBUTION

As seen in the Jun-2015 edition of the

Lean Management Journal

Continuous Improvement (CI) is a well-established concept within organisations. Many have developed elaborate CI strategies and transformation programmes. However, in our opinion, there is a fundamental problem that advocates of CI need to address. How successful have we been as a CI community in really improving organisational practice and outcomes?

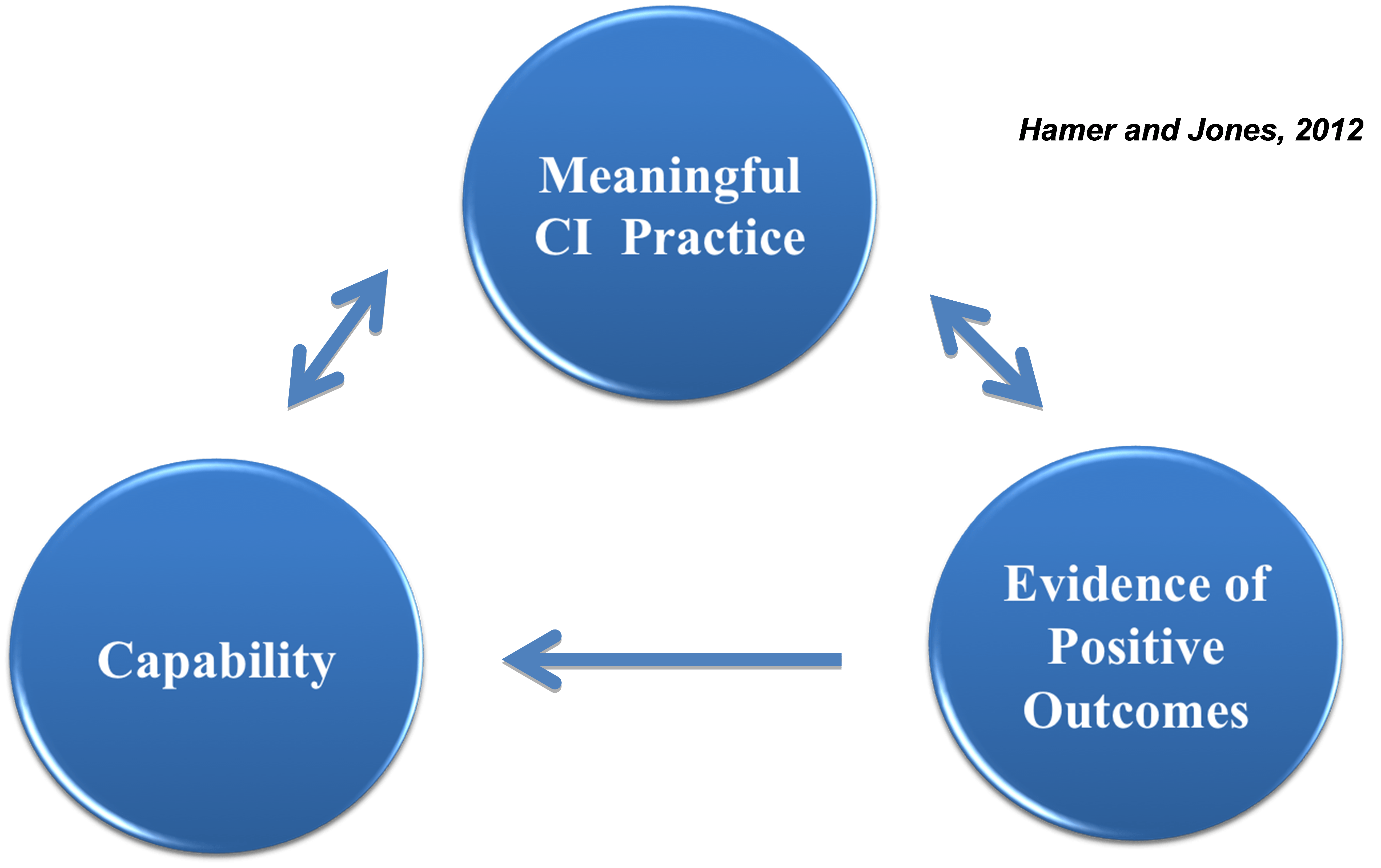

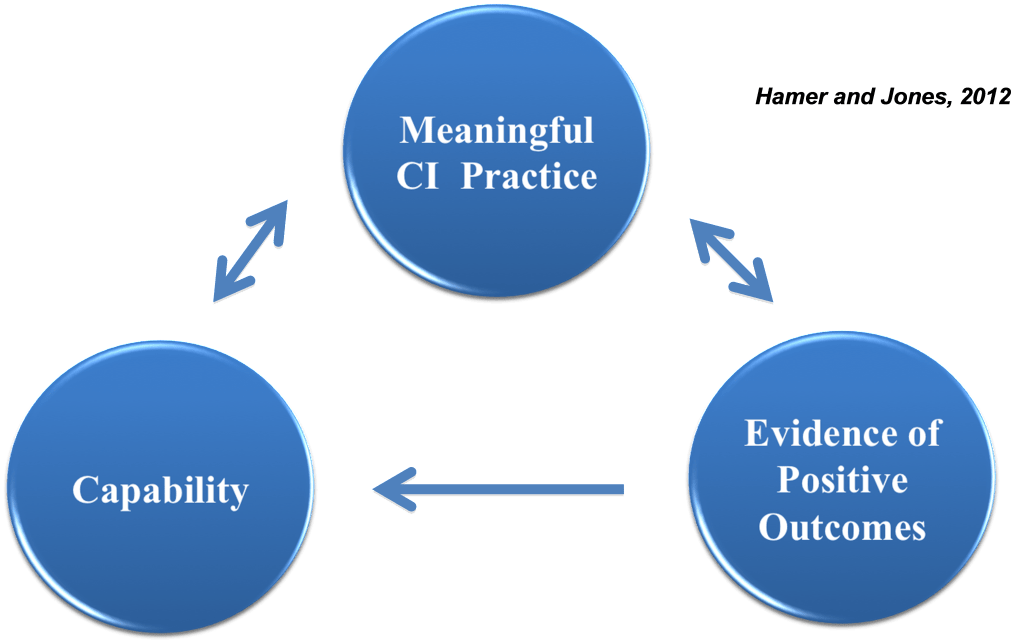

We believe that in order for CI to transform organisations, a balanced contribution of capability, meaningful practice and evidence of positive outcomes is required. We will explore the model in more detail and present thought-provoking questions that we, as CI Practitioners, should be asking. This article specifically focuses on capability.

‘Capability’ describes an organisation’s understanding, readiness and commitment to transformation, together with its skilled resources to achieve this. A capable organisation should have the right people, in the right number, with the right skills, in the right place, at the right time.

We argue that organisations are failing to develop real capability because they believe, despite the evidence, that capability is achieved by training. Training is excellent at providing delegates with facts quickly and cheaply. It is also the best way for managers to demonstrate their competence in organising activities for workers. However, real capability is about changing the normative and cognitive landscape. Normative means how people are motivated and expected to behave and how they expect others to behave. Cognitive means how people think about their work. Traditional training is nearly useless at achieving normative and cognitive transformations.

It is useful to differentiate between competence and capability. If competence is the individual’s acquisition of knowledge and skills, then capability is that person’s confidence in applying these knowledge and skills. It is the extent of someone’s ability to do something and has direct effect on a person’s productivity and performance.

Training alone does not equal capability. Learning facts, skills and building knowledge that are not practised is wasteful in itself – indeed this is part of the argument which the CPO model is based around. One way of building true capability may be to enable normative experiences – in other words learning by doing and experiencing, after all isn’t this the premise upon which CI is founded?

So why is it then that some organisations find it difficult to just “have a go”, build a prototype or pilot an idea or concept? Maybe it’s because building this type of capability building takes courage and is often associated with failure itself. For some organisations, particularly public sector, the risk of “getting it wrong” may be too great.

Without doubt, every organisation needs time to develop CI capability, which changes over time. Typically, organisations start by focusing on developing knowledge and experience across the organisation. There are different approaches to developing capability; arguably the most effective CI programmes focus on developing Line Managers CI capability by putting the learning into practice through problem-solving those processes which the Line Managers are responsible for. Learning by doing and mentoring is key.

To strengthen or enhance this capability and learning even further, some organisations choose to rotate their line mangers to other parts of the organisation so that they learn to apply the thinking to new areas of the business – helping to close any capability gap across the organisations

The role of leadership must not be under emphasised and is indeed a form of capability in itself. Leaders do not need to understand the CI tools and techniques in detail – but they do need to recognise where CI knowledge and experience has positively impacted the customer through effective problem solving. An important part of the leader’s role is to reward this behaviour appropriately.

The true measure of CI capability should focus on developing CI knowledge and understanding of line mangers and frontline resource, which can be achieved through capturing and sharing knowledge, as well as success/failure stories. Capable line mangers and frontline workers have the ability to solve problems for themselves, in line with true business outcomes. It should not about certification in CI practice or accreditation against a certain level or belt.

At an organisational level there is a need for CI capability to be distributed across teams and departments. It goes without saying that different roles require different skill sets and therefore capability building will be different at each level of the organisational hierarchy. For systemic change this capability must be distributed across the network or system, and furthermore is must be properly aligned.

Technological advances, global markets and increasingly sophisticated customers have resulted in many organisations working across networks, with boundaries becoming blurred and agendas becoming more integrated that ever before. Effective, efficient supply chains require improvement at a holistic level and therefore CI capability must be developed with this in mind. Arguably CI needs to start somewhere and, as already mentioned, typically at a local level. However, the more joined-up and integrated this capability becomes across the supply network or system, then the greater the opportunity to truly transform organisations and deliver services differently. Communities of practice are a great way to build capability across networks and systems.

Two questions that we encourage CI leaders and practitioners to ask themselves before building CI capability are:

- How do we measure CI capability?

- How do we sustain this capability to enable long-term improvements that deliver positive outcomes?

Building real CI capability is more difficult than it sounds. Training alone will not lead to capability. Learning by doing is essential, and Leaders need to accept that we learn from our mistakes as well as successes. Capable CI line mangers and frontline workers have the ability to solve problems for themselves, in line with business outcomes. Put simply, you can only measure CI capability by changes in the way that people think – their cognitive attributes, which is evidenced by the way that they behave – their normative commitments. Training and accrediting tens, hundreds, or thousands of employees is irrelevant and indeed an archetypal example of waste, if there is little behavioural change.

Similarly, sustaining change is a matter of commitment, and commitment is a cognitive attribute. Where organisations do not embed or sustain lean practice, it can only be because they prefer to prioritise alternative commitments, usually to the status quo or to established ways of managing that place more emphasis on Control, Status and Identity than on eliminating waste and improving service for the benefit of customers. A virtuous circle is established between normative and cognitive change in the sense that the best way to change thinking is through the positive reinforcement of the benefits secured by changing the way that people behave within organisations.

The most important thing that we can say about creating capability is that training is not a solution, it is the problem. We need to abandon training and start to think how we can design normative experiences that provide people with the opportunity to solve problems for themselves. The next, and possibly hardest step, is to recognise that if people do not start solving their problems for themselves, it is probably because the management system is actively preventing them from doing so.

By Rhian Hamer and Owen Jones

Dr Owen Jones is a Senior Lecturer in Service Improvement and Programme Director

Dr Owen Jones is a Senior Lecturer in Service Improvement and Programme Director  of the MSc in Continuous Improvement in Public Services at the Business School.

of the MSc in Continuous Improvement in Public Services at the Business School.

Owen has also consulted and trained on behalf of a wide range of public and private organisations over a twenty year period in the fields of supply chain integration, lean production and supply, developing and sustaining co-operative relationships and enhancing public value through continuous improvement and service transformation.

Rhian Hamer, associate fellow, from University of Buckingham.

CONTENT PARTNER CONTRIBUTION

CONTENT PARTNER CONTRIBUTION

As seen in the Jun-2015 edition of the

Lean Management Journal