What is the Effect of WIP on Process Cycle Times?

I hear people talking about “WIP” and I have to say that I have no Idea what they are talking about. Also, I hear this “WIP thing” used when they want to reduce the time it takes to do parts in a manufacturing plant. What are they talking about, and how can this help me speed up my game by improving customer delivery times? We are in danger of losing some customers if we don’t improve our “on time” customer deliveries; and this could be catastrophic in today’s economy. Further, we are trying desperately to maintain a credible business reputation, but we can’t seem to be able to predict and/or control our process times in manufacturing and the office. Our team (10 people) holds a daily morning meeting (usually 45 minutes long) to uncover some of the root causes and make changes, but we are still delivering “late” and our Sales people are continually apologizing and offering concessions to make up for our poor and inconsistent performance. Lately, my entire day is filled with fire fighting related to delivery and “on time” performance issues. Please help!

Lean Champion’s Answer:

I feel your pain! Let’s see if I can help.

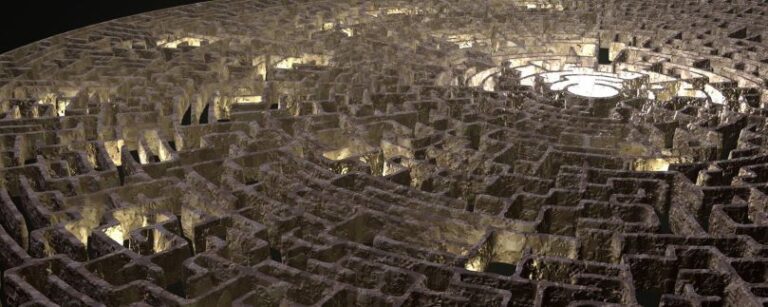

WIP is known as “Work in Process”. WIP is the inventory between the start and end points of a product routing. It does not include work in stock points. WIP can apply to manufacturing or other processes (such as an office process). In other words WIP is “stuff” being worked on that is not in a “stocked situation”. WIP is an important parameter because it affects the time it takes to process parts through the system and critically affects ability to maintain quoted lead times. A law known as “Little’s Law” pretty much tells the story. Little’s Law is: Cycle Time (CT) is equal to the WIP devided by Throughput (TH). Cycle time (CT) is the process time while the product is in WIP. Throughput (TH) is the inverse of cycle time. For Example, if a process takes 0.02 hours per part, then the throughput is:

(1 part)/(0.02 hours ) = 50 parts per hour through that process

Let’s say you have 500 parts in process (WIP) and your process is capable of doing the above 50 parts per hour (TH). By Little’s Law we can predict that this process will take:

(500 Parts WIP)/(50 Parts per hour TH) = 10 hours (for 500 parts)

Note: cycle time and throughput are on a “time basis” of hours; units must be constant for the formula to work correctly. You can work in minutes or days or any other time unit as long as you are consistent throughout the formula.

Now you can see that your factory is loaded for the next 10 working hours and if part sequence number 501 comes in you can tell the customer it will take 10 hours (queue time) + .02 hrs. (part process time), or, 10.02 working hours to produce at your present rate of 50 parts per hour with 500 parts ahead of it. (Don’t forget to add non-work times for “calendar time” estimates). The 10 hours (queue time) will cause new orders to wait unless something is done to increase the throughput or invoke “passing” (where part sequence no. 501 jumps ahead of all or part of the preceding 500 piece order). The problem with passing is that it can make other orders late. If 10.02 working hours is unacceptable to the customer, then you will have to pull a “capacity trigger” (assuming “passing” is not acceptable) in order to shorten the 10.02 hours to an acceptable level. Capacity triggers increase throughput, and consequently reduce overall cycle time, to produce the parts in queue for a given amount of WIP.

Little’s law is physical law, and will prevail over the long run, so it helps us plan and improve our work; however, if we ignore it, the results can be very disappointing. If WIP increases without adjusting throughput, our cycle times can easily go beyond acceptable limits. The key is knowing “real time” when this is happening so you can react (without over reacting by spending too much money). Conversely, if WIP is reduced below “critical levels”, throughput, and thus revenue, can decline. “Critical WIP” is the WIP level where cycle time is minimum and throughput is maximum. Indeed, this is a delicate balance, but with the right metrics and “on the floor” visuals this is certainly possible (even in mixed model and custom environments). Using these principles, I was able to help a company drop total cycle time from 67.88 hours to 11.30 hours- an 83.3% improvement (six times faster than the original time). Always remember; you can’t improve what you don’t measure, nor can you manage something unless you have a way to measure it.

Jim McCarthy is President and Owner of Product Ventures, Inc., a consulting company for “World Class” office & manufacturing improvement located in Eden Prairie, Minnesota. Certified: Lean Master. 6 Sigma Master Black Belt, Lean Leader, Lean/Six Sigma Practitioner, Lean Office Practitioner, Quick Response Manufacturing(QRM) Implementer and High Performance Leader

Contact Jim McCarthy at: mccarjfm@aol.com