SMED; A Different Perspective

A lot of people already know about Single Minute Exchange of Die (SMED), which is sometimes called Quick Changeover, and the traditional application of it. But anyway, I will briefly explain about the methodology and how to apply it. And then I will tell you about a case where I really had to turn everything concerning SMED on the head. At least in my own head.

The SMED methodology

The SMED methodology has been in use for a long time now. It originates from Japan and has been used in Toyota for many decades. Shigeo Shingo is the originator of the methodology and he is known for reducing the changeover times on presses and other machines with up to 94%. These types of results woke the general interest in learning how to reduce change over times in companies all over the world. Especially companies that want to apply the JIT (Just In Time) philosophy where you want to deliver in smaller lot sizes to satisfy the costumers demand. That often means you have to change products over more often and therefore you want to reduce your change over time.

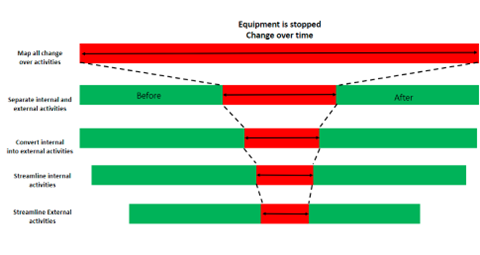

The idea behind SMED is super simple: you want your machine to stand still as little time as possible! That’s it! The less time you spend changing over the more capacity you can free up to run the machine. The methodology is quite simple as well: you work intensely on moving all other activities than the actual changeover to be done either before or after the changeover activity. The activities where the machine needs to stand still are called “Internal” and the activities that can be done before or after are called “External”.

There are six activities in the SMED methodology:

- Map and time all activities

- Separate activities in internal and external activities

- Convert internal activities to external (where possible)

- Streamline remaining internal activities to minimize change over time

- Streamline all external activities

- Document and train operators in the new process

So needless to say, the critical resource is time and we therefore want to reduce the time the machine is stopped to a minimum.

A different perspective on changeover times and SMED

This brings me to the case that I wanted to talk about. The industry is railway and the work is maintenance. What happens is (as happens with your car as well) that at some certain point in the life of a train is has to go into service, for instance each 50.000 km, 100.000 km, 300.000 km. Depending on the mileage the service contains different activities. In this case at let’s say each 100.000 km the train set needs to change its motor unit. The motor unit contains the motor and other essential functionalities.

I and the production leader Kent Armstrong who was responsible for the service operations were presented with a challenge from management: “It takes way too long and we spend way too many resources when we change the motor units on the train sets. We need to do it much faster and with fewer resources”.

So, this was our challenge but first I will explain the process for changing the motor unit.

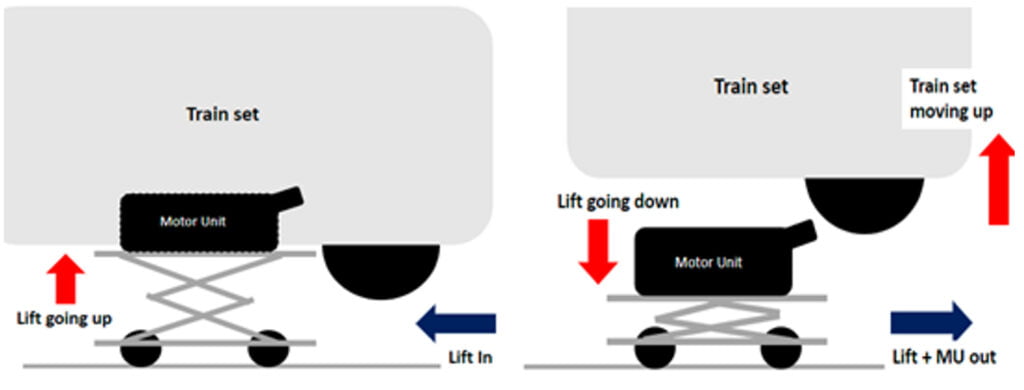

The process is that the motor unit is demounted on a lift and then the train is raised into the air until the lift and the motor unit can be moved away under it. Then the new motor unit is moved in and mounted again beneath the train in the same manner. Not that complicated right?

Lift going in and lifted up, then demounting of the motor unit Lift going down and train set moving up and motor unit + lift out

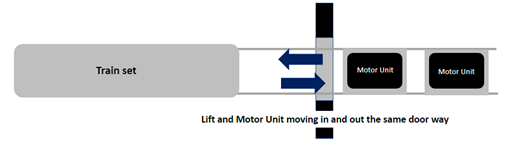

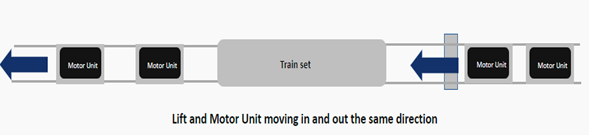

But then add that the lifts have to go the same way that it went in and that only two motor units can be placed outside at the same time. And that you have three craftsmen working on each motor unit and that there are four motor units for each train set. Ah yes of course all motor units have to be demounted before you raise the train and still you can only move two motor units out at a time that has to be picked up by a forklift and moved away into a rack. This has to be done for all four motor units before they can load the new motor units onto the rail and then moved in under the train set.

This process could take up to 16 hours (typically 12 hours) in which there were a lot of waiting for the guys (at least 12 craftsmen waiting and not doing anything value added work as such.

As you probably can see the process is clearly a changeover. A changeover of motor units, yes but still a changeover. So according to the SMED methodology we should reduce the internal activities and the time that the train stand still. But hold on! The train stands still all the time, I mean it is supposed to: it is going through the planned service. I pondered over this for some time and I knew I was on to something: using the SMED principles. But how? So, what to do?

I had to take my own medicine and go to the Gemba! I always say to my coachees: if in doubt always go to the Gemba, the truth is on the Gemba! I therefore stood and watched the process again, and I watched how the guys worked hard on demounting the motor units and gained time, but then came moving out the lifts and motor units, waiting for the forklift lifting old units off the rail putting them into the racks, fetching new units in another rack etc. And the guys stood still impatient to get moving. And then it dawned on me: the guys were the “internal resource” that we wanted to be active all the time. And this idea was even more clear to me when I read an article about the story of the lake and the rocks. I think everyone reading this article must know the allegory that we lower the water to find the rocks, cut off the rocks and then lower the water again. The idea is to lower the inventory so that we find problems, deal with them and lower the water even further. But then the article surprised me. We lower either the inventory or the manning. Aha!

With the before mentioned challenge from management: “it takes too long and you use too many men” we now had a clearer picture of what to do. So, we used the SMED methodology and made sure that preparations were made: we opened up a new track to put in the new motor units so that they were ready when the change was to take place. We then investigated how we could move the motor units in the same direction as this would reduce the changeover time the most. We knew there were some tracks in the pavement on the repos and found out that this could be used and then we had to take some measures with the forklift that was running on gas (the electrical ones didn’t have enough muscles to lift and move the units. We made some kind of tube that could be coupled with combustion tube so that there were no fumes from the forklift.

And the result was that we reduced the changeover time by between 33-50% in less than eight hours and removed one guy on each motor unit so that we ended up at only 8 guys working on demounting and mounting the motor units.

So, this case shows how I really had to turn things around in my head to solve the management challenge of a process that “takes too long and spend too many resources” using SMED.

This story just shows how Lean Thinking can be applied to any setting. It is really “just” a matter of challenging yourself to find the right thinking and thereby uncover the right solutions.

About the Author:

Erik holds a B.Sc. Eng (Production) Hons. and Diploma in Supply Chain Management and has been working in the area of CI and Lean the last 20+ years. He has held several managerial positions in a variety of companies and has worked as an internal and external consultant in private, public, and semi public companies working with the optimization of processes and improving the bottom line.

Erik is currently the Operational Excellence Manager at Stryhns AS.

LinkedIn Profile; https://www.linkedin.com/in/erikthansen/