How you communicate is more important than communicating

Communication, quite simply, is the act of transferring information from a source to a destination. And those who lead – as well as those who aspire to lead – must recognize and understand the importance of communication, as well as gain a command of the skills to communicate effectively.

The variety of the “envelopes” – the packaging in which communication is delivered – is nearly infinite. For instance and to present just a few; information can be communicated in the form of poetry – in which the nature of the information being conveyed can be rather abstract and thus lend itself to being inferred and debated until the end of ages. Compare and contrast this with prose, which delivers information in the form of story-telling. Then there is the non-written communications in the arts and even body-language, where the information being conveyed is much more nuanced and subject to wide interpretation.

There is also a significant difference between communicating base elements of information (such as facts, trivia, data, and instruction) as compared with more complex forms of communication (such as ideas) – although achieving both is sometimes possible.

As an example of how lofty ideas can be expressed succinctly, we can look no further than the two speeches consecrating the National Cemetery at Gettysburg at the sight of the Battle at Gettysburg. One by the Honorable Edward Everett (who had been a politician of stature from Massachusetts, an Ambassador to the United Kingdom, and a Secretary of State – and was considered a gifted orator though he held no office at the time), and the other speech delivered by Abraham Lincoln (who was then the President of the United States).

Everett spoke first, delivering an oration entitled “The Battles of Gettysburg”, which was 13,607 words in length and took over two hours to deliver. Neither the man, Everett, nor his oration is remembered by anyone except the odd historian who might take interest in these particular circumstances – and the power of archiving such history in the internet. Google never forgets.

Lincoln’s “Gettysburg Address”, was 271 words long in total and took a mere few minutes to deliver. Of the two men and their speeches given, which are remembered?

“Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battlefield of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate, we can not consecrate, we can not hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

But we all are not Abraham Lincoln – and few of us have the talent and ability to wordsmythe as he did. Sadly but realistically, the people with whom we communicate will most likely not have their spirits transported to a heightened state of consciousness or enlightenment as a result of our communication (although we might want to think as much). So if we are to be leaders, we better learn how to communicate as leaders should – with efficiency and effectiveness.

Clarity of Content

“Elegance is achieved – not when there is nothing more to add – but rather when there is nothing more to take away.” – Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

As professionals of Operational Excellence, we strive to create the most elegant solutions possible in our processes and in our systems. So, why not strive for the same in the manner in which we communicate? After all, I would argue that if you are going to convey information or offer instruction, you must keep the message and content clean, simple, and concise to maximize the opportunity of the information being received and retained by the recipient as clearly as originally intended.

For an example, we can examine the idea of “Standing Orders” (also known as “General Orders”) in the Military. Standing Orders are orders (instructions) that just exist – plain and simple – and which must be followed by everyone without further instruction or direction. You can think of them as rules to live by on an everyday basis. For instance, a “standing order” at the Paris household when I was growing up was to “make my bed and brush my teeth”.

Standing orders are not complicated and are easy to understand. All one has to do to make them effective is to memorize them and perform as directed. Their simplicity is their charm and is what makes them attractive and memorable.

We can compare two; one is a list of the Standing Orders for Roger’s Rangers developed by Major Robert Rogers for his troop’s use during the French and Indian War. And the other, which is more contemporary and will probably resonate with more of you is “Gibbs’ Rules” from the television show NCIS.

STANDING ORDERS, ROGERS’ RANGERS

– MAJOR ROBERT ROGERS, 1759

Ranger Handbook

- Don’t forget nothing.

- Have your musket clean as a whistle, hatchet scoured, sixty rounds powder and ball, and be ready to march at a minute’s warning.

- When you’re on the march, act the way you would if you was sneaking up on a deer. See the enemy first.

- Tell the truth about what you see and what you do. There is an army depending on us for correct information. You can lie all you please when you tell other folks about the Rangers, but don’t never lie to a Ranger or officer.

- Don’t never take a chance you don’t have to.

- When we’re on the march we march single file, far enough apart so one shot can’t go through two men.

- If we strike swamps, or soft ground, we spread out abreast, so it’s hard to track us.

- When we march, we keep moving till dark, so as to give the enemy the least possible chance at us.

- When we camp, half the party stays awake while the other half sleeps.

- If we take prisoners, we keep’ em separate till we have had time to examine them, so they can’t cook up a story between’ em.

- Don’t ever march home the same way. Take a different route so you won’t be ambushed.

- No matter whether we travel in big parties or little ones, each party has to keep a scout 20 yards ahead, 20 yards on each flank, and 20 yards in the rear so the main body can’t be surprised and wiped out.

- Every night you’ll be told where to meet if surrounded by a superior force.

- Don’t sit down to eat without posting sentries.

- Don’t sleep beyond dawn. Dawn’s when the French and Indians attack.

- Don’t cross a river by a regular ford.

- If somebody’s trailing you, make a circle, come back onto your own tracks, and ambush the folks that aim to ambush you.

- Don’t stand up when the enemy’s coming against you. Kneel down, lie down, hide behind a tree.

- Let the enemy come till he’s almost close enough to touch, then let him have it and jump out and finish him up with your hatchet.

GIBBS’ RULES, NCIS

– LEROY JETHRO GIBBS

The NCIS Database

- Never let suspects stay together.

1a. Never screw (over) your partner. - Always wear gloves at the crime scene.

- Don’t believe what you’re told. Double check.

3a. Never be unreachable. - If you have a secret, the best thing is to keep it to yourself. The second-best is to tell one other person if you must. There is no third best.

- You don’t waste good.

- Never say you’re sorry. It’s a sign of weakness.

- Always be specific when you lie.

- Never take anything for granted.

- Never go anywhere without a knife.

- Never get personally involved in a case.

- When the job is done, walk away.

- Never date a coworker.

- Never, ever involve lawyers.

- Bend the line, don’t break it.

- Always work as a team.

- If someone thinks they have the upper hand, break it.

- It’s better to ask forgiveness than ask permission.

- Always look under

- Never, ever interrupt Gibbs in interrogation.

- Never mess with a Marine’s coffee if you want to live.

- There are two ways to follow someone.

1st way – they never notice you;

2nd way – they only notice you. - Always watch the watchers.

- If it feels like you’re being played, you probably are.

- Your case, your lead.

- There is no such thing as coincidence.

- If it seems like someone’s out to get you, they are.

- Don’t ever accept an apology from someone that just sucker-punched you.

- First things first, hide the women and children

- Clean up your messes.

- Sometimes – you’re wrong

- Leave room for someone exiting the elevator.

- Never trust a woman who doesn’t trust her man.

Each of the above, whether you are in the military and familiar with the Ranger Handbook or a domestic observer watching NCIS, is easily understandable and crystal clear in their intent. So certainly, to be an effective leader, your communications must possess a clarity of content.

Perspective

“Our experience of many life circumstances is a function of our personal perspective and not the circumstance itself.” – Lindsay Wagner

But clarity of content will result in only partial success. Certainly, a communication that is crisp and succinct will be easily understood – but how do you get the people receiving the communication to act as intended?

Will they do what is being asked? Do they even understand what is being asked? Do they have the competence to carry-out any instructions that might be contained in the communication? Will they follow the instructions faithfully and thoroughly? What if that which is being communicated is more nuanced or abstract than a “do this task this way”? Do they feel they can ask questions, seek help, or even offer constructive criticism?

When you communicate, do you assume too much? What about the context? Does the communication take into consideration the circumstances effecting the recipient? Are there traditions, nostalgias, or infrastructures which might influence their opinions or actions? Are you listening to what is being said back to you? Not just hearing, but actually listening? Are you taking the opportunity to truly understand the input?

In this case, understanding “perspective” is all-important.

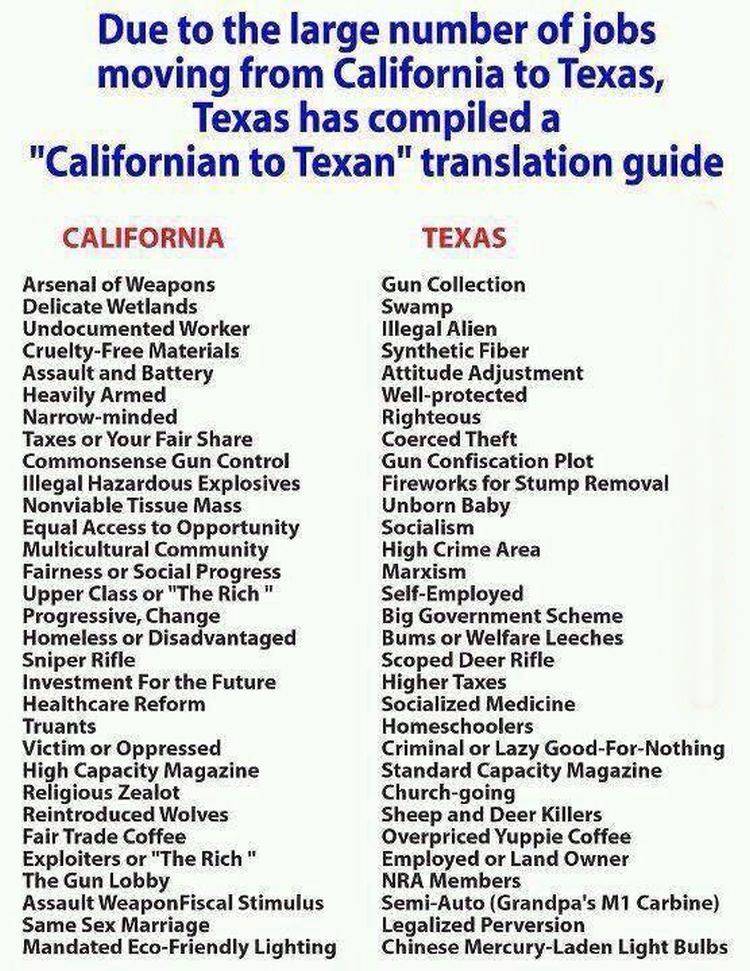

I recently came upon a post on Facebook whose major premise was that a “large number of jobs” were moving from California to Texas – along with a handy “translation guide” for Californian phrases into Texan (presumably to help with integrating Californians to Texas).

To me, it snapped into focus the importance of how you communicate your message, not just the message, and I decided to conduct an informal poll of my “friends” to gain their opinion.

One person didn’t see the point I was trying to make and focused on the title. But instead of using “large number of jobs”, he decided to invoke the word “stampede”, which has an entirely different tone and emotion than what was being proposed, noting that; “The interesting thing about this widely held belief (a CA to TX migration stampede) is that the numbers don’t back it up. In 2012, net migration … was about 19,000 going from California to Texas – and that’s not isolated to 2012 either.”

He did not cite where he obtained his numbers (however, he is usually pretty accurate). But, my response was, “If I saw a herd of 19,000 coming towards me, I would call it a stampede.”

The more interesting observation was that the others who participated in my little experiment did not align themselves with what they were “for”, as much as what they were “against”.

For instance, those who would align themselves with that of a Californian and (generally) against the ownership of guns would tend to think of “arsenals of weapons” and “sniper rifle” rather than “gun collection” and “scoped deer rifle”.

Whereas those who might align themselves with that of a Texan and (generally) against taxes would consider taxes “coerced theft”, whilst a Californian would tend to think of taxes as “paying your fair share.”

What is “right” (or at least what you believe is right) depends on your beliefs and will stir your emotions and motivate you – with the intensity of these reactive emotions increasing as the strength you might have in any particular belief increases. Think about your feelings this very moment given the two examples I cited above. For which do you have more intensity; the statement that resonates with you or the one that is in opposition to your beliefs?

Being “for” is natural – an expectation. We assume that everyone “in their right mind” should just hold the same position or opinion as you do because – just because. So, when someone says something with which we agree, we pay it no attention. However, when presented with a position or opinion with which you are opposed, it garners all manner of attention – because it’s a challenge to who we are.

Mostly, as people, we normally do not challenge “laws of nature”. We believe that if we drop something, it will fall due to gravity (never-mind that in the purest terms, an apple falling to earth would also see the earth falling towards the apple). Or that something that is moving will tend to continue moving unless stopped.

But “laws of man” are made by man and can be bent or broken by man.

For instance, prior to 1974, the speed limit on highways in the States was up to 80mph. But in 1974 and with the premise of increasing fuel efficiency in the wake of the 1973 Oil Crisis and in the interest of public safety, then President Richard Nixon signed the National Maximum Speed Law, which made 55mph the maximum speed allowed throughout the States.

In 1987, the law was changed so that the speed limit on rural interstate highways could be 65mph – and the law was changed once again in 1995 which returned governance of speed limits back to the individual States. It should be no surprise that the Lone Star State, Texas, has the highest speed limit of all the States; at 85mph.

How could this be explained? Were the highways suddenly safer than before? Was there no longer a threat to the energy supplies?

Simply put, there was a change in perspective as a result in a change in circumstances.

When it comes to “laws of man”, there is no “right” or “wrong”; there is just what wisdom a person might have and what beliefs they might hold.

Lessons learned;

Perhaps, if I were to write this article again, I should just write;

“In your communications with others; be clear and concise – and don’t assume the recipient will possess your knowledge or share your beliefs.”

By Joseph F Paris Jr

Paris is the Founder and Chairman of the XONITEK Group of Companies; an international management consultancy firm specializing in all disciplines related to Operational Excellence, the continuous and deliberate improvement of company performance AND the circumstances of those who work there – to pursue “Operational Excellence by Design” and not by coincidence.

He is also the Founder of the Operational Excellence Society, with hundreds of members and several Chapters located around the world, as well as the Owner of the Operational Excellence Group on Linked-In, with over 45,000 members.

Connect with him on LinkedIn