The Imperatives of Smart Improvement: From Better Sameness to Transformation

75 percent of improvement projects fail.

That’s the number most academics and consultants believe is the average failure rate for performance improvement projects. Three out of four don’t achieve their promised objective. It’s an extraordinary waste of enterprise resources and unintended cause of employee cynicism.

The best way to improve the success rate of improvement projects is to understand why the rate is so low. Here are the ways to improve your success rate, the imperatives of transformation.

KNOCK DOWN YOUR SILOS

What do those hundreds of emails you get and the endless meetings you attend have in common? They are all attempts to connect work across organizational barriers. The emails ask for information, and the meetings connect the dots between different parts of the organization. All that communication and meeting represents the organization frantically trying to put Humpty Dumpty back together again.

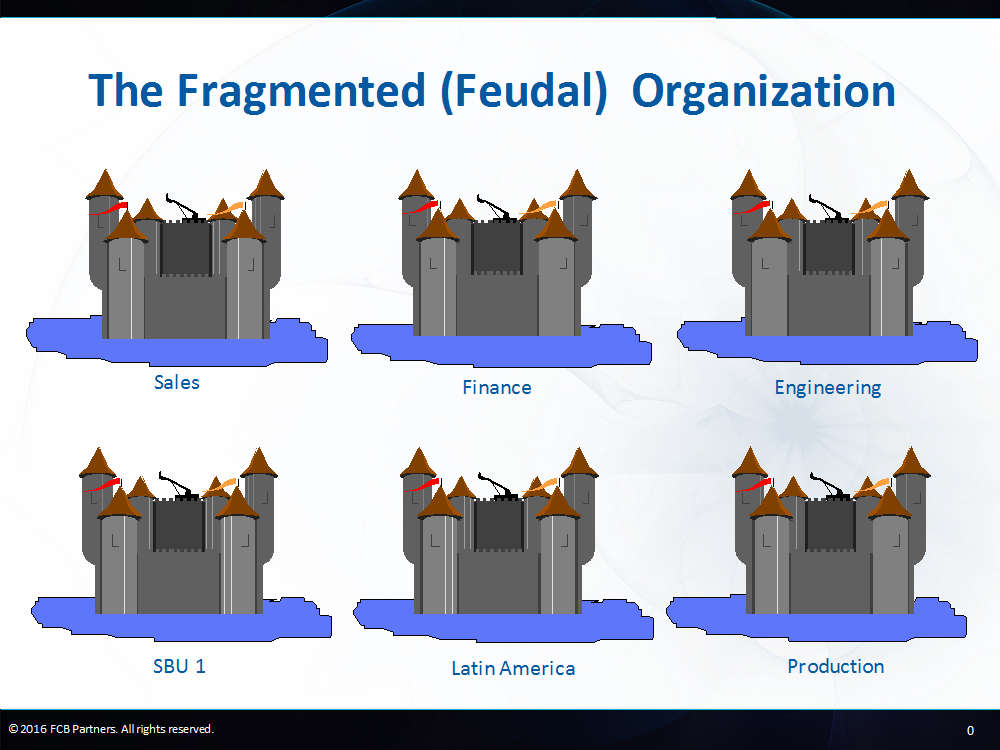

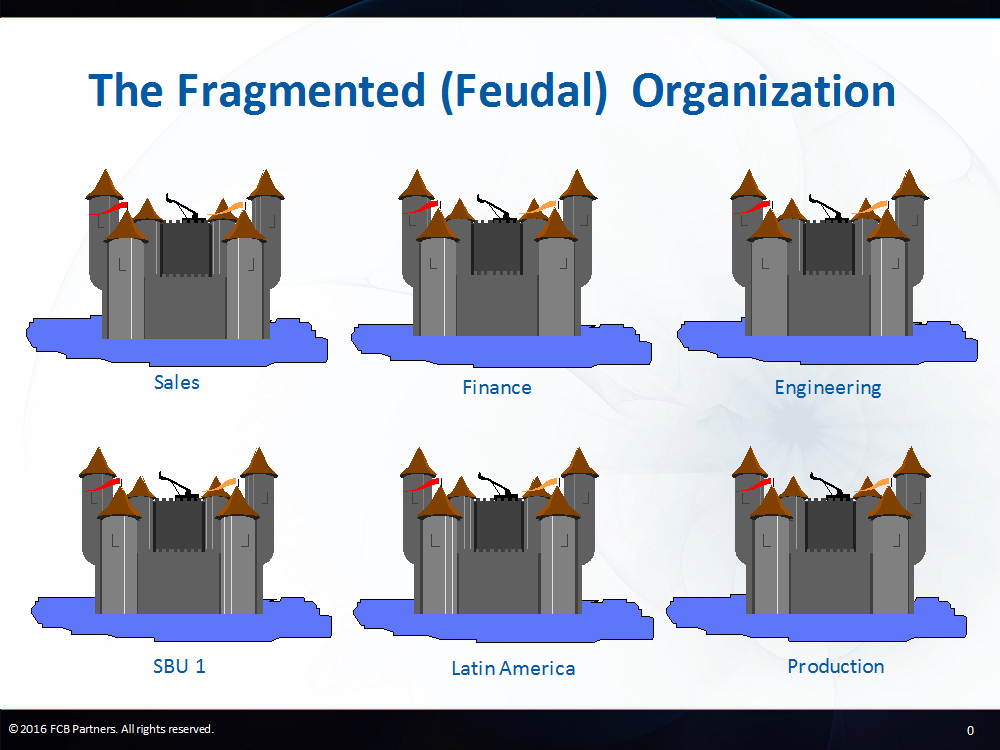

Organizational fragmentation is the single biggest cause of poor business performance. Fragmentation, the opposite of synergy, occurs when the whole is far less than the sum of the parts and thrives when success is defined locally. When small fiefdoms litter the enterprise, the organization splinters, leading to the triumph of the parts over the whole.

It’s organizational feudalism.

To better understand the fragmentation within your organization, consider this updating of the fable of the Six Functional Workers and the Order Fulfillment (OF) process:

- One worker looks at OF and says, “It’s all about inputs, therefore raw material costs are the key metric.”

- The second says, “Inputs are of zero value unless they are moved to where they need to be, therefore logistics is the centerpiece of OF and on-time delivery is the right metric.”

- The third says, “Obviously you’ve never been in a manufacturing plant; that’s where all our capital is tied up, so long production runs are critical to achieving low unit costs.”

- The fourth says, “You guys are all nuts. Without quality, we’re nowhere; just do what I tell you to do, and measure variations.”

- The fifth says, “Without a bill we’ll never get paid, so invoice accuracy is the best measure.”

- The last says, “I’m from Sales, how come none of you bozos said anything about the customer?”

Another way to visualize fragmentation is to think about the span of work that connects you with your customer. From the moment you receive an order to the time that order is fulfilled, how many parts of the organization get involved? How many boundaries must be crossed and how many hand-offs are required? For most organizations, the answer would be at least 10 to 20 different departments. At a large consumer products company, 25 separate functions were involved.

Who in your organization is responsible for integrating all those disparate departments into one seamless whole? Whose job is it to put Humpty Dumpty back together? Your CEO’s? No one’s? Maybe Exhibit 5, created by Dr. Michael Hammer, can further help you visualize fragmentation.

You cannot expect all that royalty to dismantle their own castles. They won’t do it; their power, prestige, and pay are derived from their territory. And the castles won’t fall down on their own—the foundations are deeply entrenched. You can’t take them down brick by brick and hope to finish the demolition in your lifetime. You must knock down those walls—forcefully. As Mao-Zedong once said, “A revolution is not a tea party.”

Whether you call them silos, stovepipes, smokestacks, or fiefdoms, the business problems caused by fragmentation are enormous. Here are just a few of them:

High costs are generated from the volume of non-value-added work required by multiple handoffs, such as the daisy chain of order fulfillment. Why so many handoffs? The culprits include multiple process versions, non-integrated software systems, different functional metrics, and siloed databases. Costs go up when there are long delays from internal bickering such as when manufacturing focuses on low cost and long production runs while salespeople demand fast turnaround to keep customers happy.

Customer dissatisfaction occurs when organizations show multiple faces to the market or when internal handoffs inflict delays onto customer transactions. As one sales manager explained, “It’s not our customers’ fault that we inflict our complexity on them.” Making matters worse, today’s customers have been trained by Amazon and Starbucks to expect nearly perfect service all the time. As one CEO of a large chemical company told me, “If Amazon can get me a $10 book exactly as I ordered in two days, why can’t we fulfill our customer’s $50,000 order as quickly?”

Invisible solutions, As Jeff DeWolf of Tetra Pak noted, “No one can see the real opportunities for improvement because the walls of our castles are so high. They’re invisible because they live across territorial boundaries.” In this fragmented world, sponsorship for transformational projects is nearly impossible because there’s never just one executive responsible for an end-to-end process. That means that committees of competing executives are required to support and sponsor a project. But a prince who sponsors an improvement project will never allow that project to demolish his castle. And because of data silos, there’s no single source of truth to align around.

EMBRACE TRANSFORMATIONAL CHANGE

It’s an unfair fight because the prevailing toolset doesn’t match up well against the problem. Today’s most popular improvement approach is Lean Six Sigma, which is a hybrid of Toyota’s Production System and statistical analysis borrowed from the Six Sigma tradition. Lean Six Sigma is an example of bottoms-up improvement methodology, which means it’s generally targeted at smaller chunks of work that are executed at lower levels of the organization. Rather than attacking the entire supply chain in a single top-down project, a traditional Lean Six Sigma approach would be to approach the problem through a host of smaller projects. The goal of all those Lean Six Sigma projects would be improve workflow and eliminate waste.

Who could argue with that? Because it works, almost all large organizations today have bundled their bottoms-up improvement efforts into overarching programs, called either Continuous Improvement (CI) or Operational Excellence (OpEx).

No matter what they’re called, however, these programs almost always produce the exact opposite of their stated intentions.

It’s a paradox. Continuous Improvement Programs, which are intended to produce improved performance, almost always create only incremental performance gains and generate little real organizational change. They don’t change the work as much as they tune and refine it. It’s evolution, not revolution.

But there’s a bit of a con game involved here. Despite the best intentions and skills of its practitioners, CI often preserves the status quo.

To those who don’t want to change, CI is safe, precisely because it changes so little. CI projects operate within the prevailing paradigm and tweak the existing design. Improvement comes from doing today’s work faster and cheaper.

But when a process is fundamentally broken, the marketplace has dramatically changed, or customer expectations have radically altered, simply modifying today’s work is worse than useless since CI projects gobble up the resources needed to drive transformational change. The illusion of attending to operational problems is merely self-protection.

Lean Six Sigma was never intended to challenge the current design of work, but it does create Better Sameness, which is a polite way of saying it rearranges the deck chairs on the Titanic.

Think about the Continuous Improvement programs in your organization. How much deep change have they generated? Have they changed organizational boundaries, redistributed power, or challenged long-held beliefs? For most, they tune but don’t transform. CI is a way to change without changing. It’s safer and cheaper to tinker than transform. CI is a brilliant defensive behavior.

Traditional organizations launch scads of incremental improvement projects, hold frequent Kaizens, gather for scrums, and host other efforts to tweak their Execution Engines. Many of these efforts succeed at their intended purpose, taking waste, cost, and time out of today’s work. But too often, small change simply isn’t enough.

It doesn’t matter if this incrementalism is driven by fears of Wall Street’s reaction to quarterly results, activist investors, sheer inertia, short-term executive compensation, or fear of the unknown. Yesterday’s designs still triumph over today’s needs.

Stepping further back, the deeper problem is neither Continuous Improvement nor Lean Six Sigma—it’s the limited toolset and mindset that organizations deploy to improve performance. When all you have is Lean Six Sigma, everything looks like potential waste. When all change is part of Continuous Improvement, there’s no room for discontinuous transformation.

To be clear, this is not perpetrated by Lean Six Sigma practitioners. In my experience, they’re a dedicated group of improvers doing their best to help their organizations or clients. Process engineers truly operate with sincerity and great intentions. It’s not their fault.

Years ago, CardX, a major credit card company, was having a customer service problem. It was taking 14 days to replace a customer’s lost or stolen credit card, while its competitors were replacing cards in a week.

CardX’s CEO called a senior team meeting to brainstorm solutions. He began by asking, “How can we go faster?” After an uncomfortable silence, one exec said he could shave 30 minutes off the time by eliminating one quality check. Another volunteered a savings of 15 minutes by cutting a second mailing address check. After a tense 4-hour meeting, the CEO succeeded in shrinking the time from 14 days to 13 days and 2 hours.

The next week, this full-page announcement ran in national newspapers: “In six months, CardX is proud to announce a six-day turnaround of lost or stolen credit cards.”

What do you think happened in six months?

If you guessed that the new cycle time was six days, you’d be correct. But how did that happen? How could a team of CardX process redesigners take eight days out of the process, when the leadership meeting had found a mere 6 hours? What changed?

Everything. In the CEO’s meeting, the question, “How can we go faster?” was heard by his executives as, “How can we do what we do today faster?” This put the senior team standing squarely in the current process design looking to accelerate the existing way of working.

After the newspaper announcement, the real question emerged. The redesign team asked itself: “What possible ways can we invent to process a card return in six days?” They began by throwing away the old model, with all its constraining assumptions, and started from scratch. No amount of tweaking or amphetamines could ever cut the cycle time in half. The team realized that only a radical change could do that. That fresh approach quickly yielded several assumption-breaking redesign ideas that solved CardX’s problem.

Business Reengineering, as originally defined by Dr. Michael Hammer and Jim Champy, arose from the needs of large American organizations to overcome Japanese competition in the 1990s. Because many Japanese corporations had embraced Total Quality Management far earlier, they were winning in sector after sector. Reengineering was a new approach intended to help American companies leapfrog that competitive disadvantage by creating dramatic process improvements that produced order-of-magnitude benefits.

One primary impetus for transformation today is the threat of disruption. It’s small crafty innovators that pose the greatest threat to large industrial-era organizations. Disruptors whose DNA is fundamentally different from traditional organizations and who operate without the weight of history are reshaping the competitive landscape. These disruptors are not using new technologies just to do what traditional organizations do a little faster or cheaper. They’re radically redefining and transforming the work. When Quicken Loans can approve a mortgage in one hour while it takes a traditional bank one month, that’s not better sameness, it’s discontinuous change.

Recent research reports have revealed a puzzling mystery. Despite decades of major spending on information technology (IT), American productivity has not improved as expected. The roster of promising new technologies is breathtaking, including advances in Artificial Intelligence (AI), mobile, social, cloud services, big data and analytics, sensors, and the Internet of Things.

In 2015, the International Data Corp. (IDC) estimated that $727 billion was spent on IT in the US. Despite that massive investment, economists have not witnessed the major productivity bump that was included in all those business cases. Possible explanations for the difference in expectations include:

- Frivolity: Workers have been spending too much time on Facebook, Twitter, and games and not using new technologies on their jobs

- Maturity: It’s too early in the life cycle of many new technologies for value generation

- Over-Hyped: The promised improvements were oversold in the first place, and the new technologies just aren’t as powerful as their vendors claimed

These may be completely or partially true, but there’s an alternative hypothesis that has less to do with IT and more to do with timidity in process innovation and redesign.

Productivity gains will always be limited when new technologies are attached to old ways of working and deployed in support of existing power structures. For example, using AI to automate a 20-year-old process design for order entry is like attaching a motor to a horse and expecting the performance of an automobile. Using an iPhone app to do exactly what a traditional SAP system would do is redundant and expensive folly.

In the technology world, we’ve repeatedly seen the “less” phenomena. Radio was wireless, cars were horseless carriages, and early ATMs were teller-less windows. We tend to see the new through the lens of the old.

That’s what most organizations have been doing with all of today’s spectacular technologies. They’ve been making bigger candles rather than inventing the light bulb. In organization after organization, great technology has been applied to mundane and incremental uses. The past shapes the future as organizational timidity constrains the potential of technology.

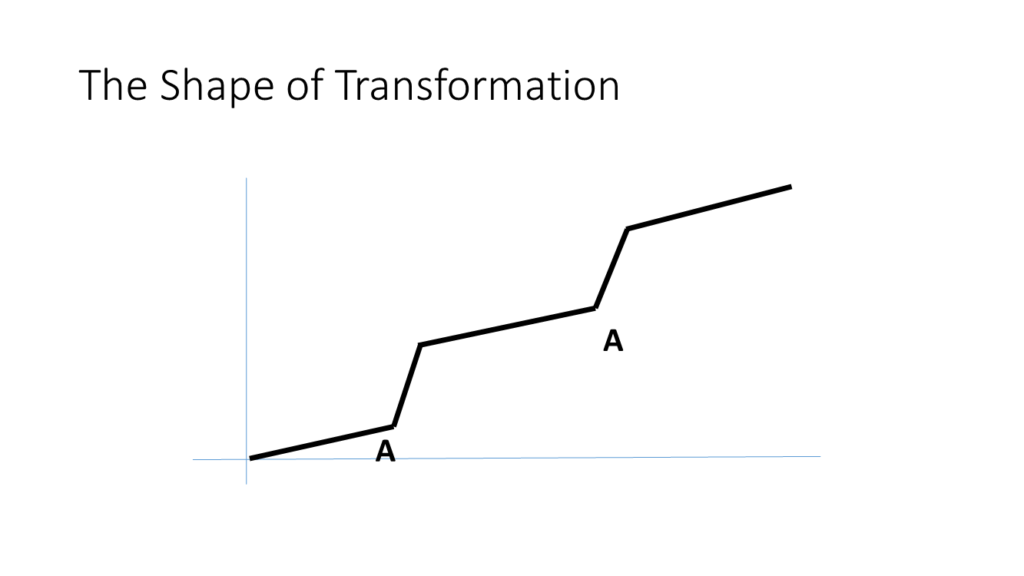

The only way to achieve discontinuous jumps in productivity is through transforming work. Consider Exhibit 7: This graph depicts the winning high jump height at the Olympics since 1900. As the graph shows, the winner for many years jumped just a bit higher that his predecessor. But twice, at the points labeled “A,” the winning jump showed a dramatic improvement—not just a little better, a whole lot better.

This graph depicts the winning high jump height at the Olympics since 1900. As the graph shows, the winner for many years jumped just a bit higher that his predecessor. But twice, at the points labeled “A,” the winning jump showed a dramatic improvement—not just a little better, a whole lot better.

What can you attribute this rapid change to? If you were a track and field expert, you’d know that these discontinuous improvements occurred when innovators came up with new ways to get over the bar, such as the Fosbery Flop where the high jumper actually goes over backwards. “What lunacy!,” traditionalists must have shouted when Dick Fosbury introduced his move. But it worked, and it was transformational.

This graph can also represent the productivity gains made possible by integrating new technologies with radical process change. When these two elements are combined, the productivity promise is solved and the paradox eliminated.

DIGITIZE YOUR PROCESSES

If you work at a large industrial-era organization, your processes were born in an age of information poverty. Because they’re relics of the Machine Age, your process designs can’t easily exploit new technologies or take advantage of today’s data-rich environment. When mapped or modeled, your processes depict tasks and physical movements instead of decisions and information flows.

We now live with information abundance. There’s data, data everywhere, and our processes need to be fundamentally redesigned to capture and use all that information to achieve high performance.

Here’s an unexpected truth. Every single dollar every organization has ever spent on hardware or software has actually been for one singular goal, the collection and use of good data. Computers and systems are merely means to an end, never the end itself. All technology allows us to do is generate, capture, and use data.

When organizations attempt to graft new technologies onto antiquated processes, it’s like motorizing a raft. The outcome is sub-optimized, and the investment is wasted. Instead of improved performance they get fossilized processes frozen in software. What good is accurate real-time data if an emergency shipment to a customer still needs three supervisory approvals or a customer service rep still needs to ask a supervisor for permission to issue a small credit to a waiting customer.

Every organization must now address the shrinking half-life of process designs. In the past, a well-designed process could last for 5-10 years without needing a fundamental redesign. But today’s turbulence has ended that stability, and as the environment is changing frequently, so must process designs.

Behind all this change is the extraordinary explosion of information technologies. Once there was a slow curve to technological maturity, but no longer. For perspective, in 2015 there were 104,000 YouTube videos streamed every second of every day. Even more extreme, Huawei, the global IT service firm Huawei estimates that by 2025, 100 billion people and things will be connected to the Internet. Everything will be wired; everything will emit, capture, and use data.

Processes must be reconceived to take into account that every movement will generate data, every object will have a sensor, and every process decision can be supported by data and measured in real time.

None of this was ever possible before.

Both process design and execution are now all about the data, as Hershey learned when it placed chocolate next to marshmallows in its retail planograms and sales of both rose (as any lover of s’mores could have predicted).

In the 1970s Walter Wriston, the CEO of Citibank, proclaimed, “Information about money is now more valuable than the money itself.” The same is now true about processes.

That’s why organizations need to digitize their processes. But what does that mean? What’s a digital process and how would you recognize one if you met it on the street?

Here are the primary characteristics of a digital process:

- From a distance, the process would pass a Turing Test, meaning that an observer couldn’t tell which tasks were done by man and which by machine.

- Immediacy, availability, granularity, utility, transparency all dramatically improve.

- The simplest tasks within the process would become autonomic, that is they would require no conscious action, creating what Doug Drolett of Shell calls a “touchless” process. This might happen when a truck finishing a delivery would automatically send a “delivered” signal, as well as trigger the sending of an invoice.

- The process would operate using actual data, not averages—the way that Progressive’s Snapshot chip senses a customer’s driving patterns and prices their policy based on that person’s specific driving skills, not on individuals like them. Other ways that actuals could replace averages might include: turning highway tollbooths into a speeding ticket machines, charging airline passengers differing fares based upon their luggage and body weight, or connecting thermostats to vending machines so that prices could rise on hot days. Actual data makes all of this possible.

- Measurement and execution would be simultaneous and interconnected, the way that Google connects and counts within a single action. This would drive a process’s ability to be self-correcting. As the process continually scans its inputs, outputs, and constraints, it could add capacity whenever needed—the way the District of Columbia’s Metro system adds cars and stations at times of peak usage. A utility’s smart grid operates the same self-correcting way.

- The tasks with the process would be both inter-organizational and disintermediated, in that sub-processes might be created or operated by different organizations seamlessly. This would take plug and play to the extreme.

- The process would be proactive and predictive. For example, if an online shopper buys hot dogs, the process may produce a prompt that suggests that they may also want buns, relish, onions, beer, and diapers.

- Its core would be composed of a data-driven algorithm as today’s airline seat pricing process is.

Pushing further, my colleague Brad Power argues, “When you digitize a process, you get big data; when you get big data, you can do machine learning; when you have machine learning, the system can get very smart on its own and continuously improve without much data scientist involvement. And when you digitize a process, it becomes software and when something is in software, it has wonderful properties such as 24/7 availability, low cost, consistency, reliability, and easy continuous improvement.”

By Steven Stanton

Steven Stanton is a NY Times best-selling Author, Speaker & consultant specializing in Management Consulting. One constant in all his work has been the facilitation of successful transformation with clients. To this end he has participated in the development and use of a wide range of pioneering methods including business re-engineering and process management. He has been immersed in process innovation and improvement for over twenty years. In addition to consulting, he has also focused on translating his experiences through writing, teaching, and speaking. He has co-authored, with Dr. Michael Hammer, the best-selling book, “The Reengineering Revolution” (HarperBusiness), as well as the Harvard Business Review article “How Process Organizations Really Work”. In addition, he has published many articles on business and process transformation in publications such as Fortune, BusinessWeek and CFO Magazine. Get in touch with him on LinkedIn.