The Need for Effective Reactive Improvement

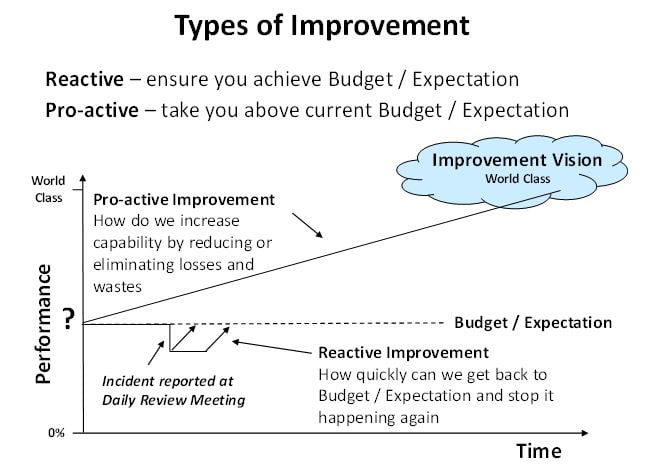

In order to achieve Operations Excellence, organisations need to be good at both Reactive and Pro-active Improvement. Unfortunately, many organisations are so focused on Pro-active Improvement through their Lean, Six Sigma and TPM initiatives that they lose sight of the importance of effective Reactive Improvement.

I often refer to Reactive Improvement as ‘below the line’ improvement as opposed to Pro-active Improvement, which is ‘above the line’ improvement in relation to the daily budgeted performance expectation.

As Pro-active Improvement gains momentum and guides you closer towards Operations Excellence, then the need for Reactive Improvement should significantly reduce. However, as a Pro-active Improvement journey can take many years to achieve Operations Excellence, there is a strong argument for getting effective Reactive Improvement in place. I have found organisations that do both are the most successful.

We have also found that effective Reactive Improvement is a great foundation for accelerating your Pro-active Improvement activities.

What is Effective Reactive Improvement?

Reactive Improvement is your ability to rapidly recover from an event or incident that stops you from achieving your budgeted or expected performance for the day and most importantly, to initiate corrective actions so that the event or incident will not re-occur anywhere across the organisation.

Reactive Improvement should be initiated whenever you fail to achieve expected performance based on agreed triggers (e.g. greater than 60 minute downtime or rework event or greater than 5% quality loss). The triggers should be set to allow sufficient problems to be addressed within resource constraints. Obviously as the triggered problems become less you would reassess and tighten the triggers accordingly (e.g. when 60 minute delays become less frequent, you would reset the trigger to a lower figure like all delays greater than 30 minutes).

The key to effective Reactive Improvement is discipline through a very effective Daily Review Process and supported by a standardised and robust Frontline Problem Solving process that is suitable for all people to be trained in – and used regularly, across the organisation.

Daily Review Process

Most organisations have daily review meetings; however, far too often they are not effective. They start late or drag on for too long, accept poor performance standards, skip over below target performance by accepting ‘work-a-round’ corrective actions, have no agreed triggers for initiating Frontline Problem Solving, and follow-up to issues raised is often done on an ad-hoc basis if done at all, with very poor monitoring or closure.

What makes an effective Daily Review Meeting?

- Agenda displayed with clear timeframe for each agenda item;

- Current performance information is updated before the meeting by attendee responsible and displayed using visual prompts (eg red is bad, green is good);

- Stand up environment (no chairs as people think and respond quicker and more distinctly on their feet);

- Clock in room (visually controlling the time of meeting);

- Starting and finishing on time (allow people to leave after agreed finish time);

- Any deviation from expectation noted with solutions taken, or if issue has not been resolved, support is allocated to assist (to be resolved outside meeting);

- Triggers for activating a Frontline Problem Solving action are displayed and regularly updated;

- If a trigger for generating a Frontline Problem Solving A3 Summary Sheet is activated, then a Frontline Problem Solving action is allocated to a designated person with timeframe for reporting back (eg within 3 working days advise outcome of Step 4 – Develop Root Cause Solutions and proposed action plan); and

- Everyone leaves with clear expectations of how their reactive problems are going to be addressed along with the required performance for at least the next 24 hours.

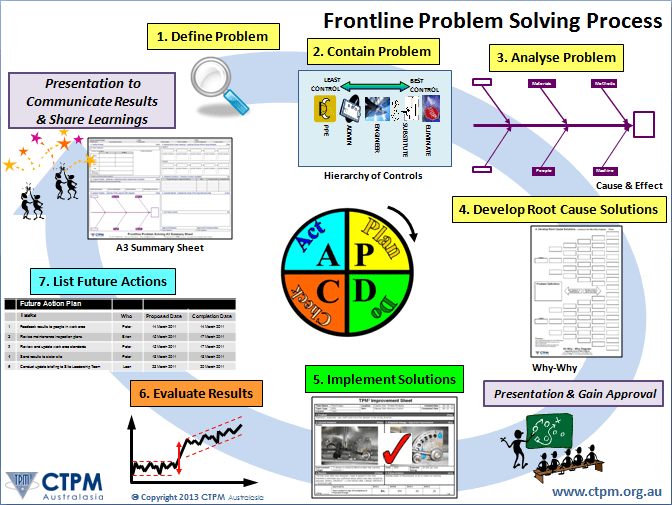

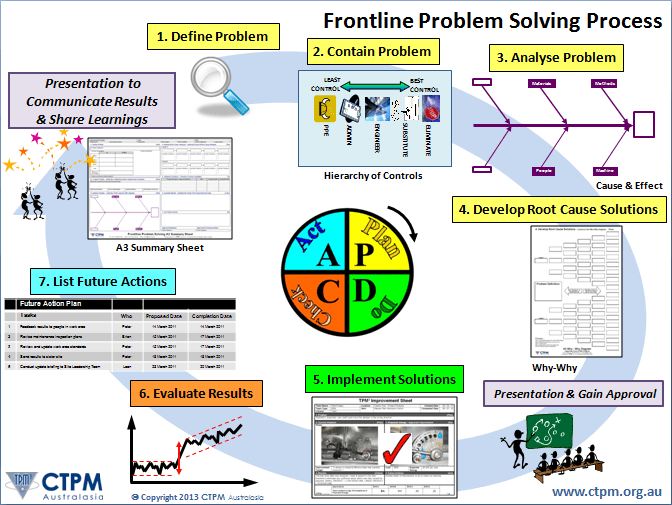

Frontline Problem Solving Process

There are many Root Cause Analysis problem solving processes in the marketplace. However, the key (as discovered by Toyota many years ago) is finding one that can be used by all people in an organisation rather than just a select few.

We developed a simple but highly effective 7 Step Frontline Problem Solving Process based on the use of Detailed Problem Definition, Cause & Effect Analysis and Why-Why Analysis that is now being successfully used by many organisations at all levels.

The key to introducing any new process into a workplace is developing an effective implementation process. Often attending a one-day or two-day workshop is a great way to be introduced to a new process, however to learn and gain confidence in a new process you need to successfully work through it at least 3 times.

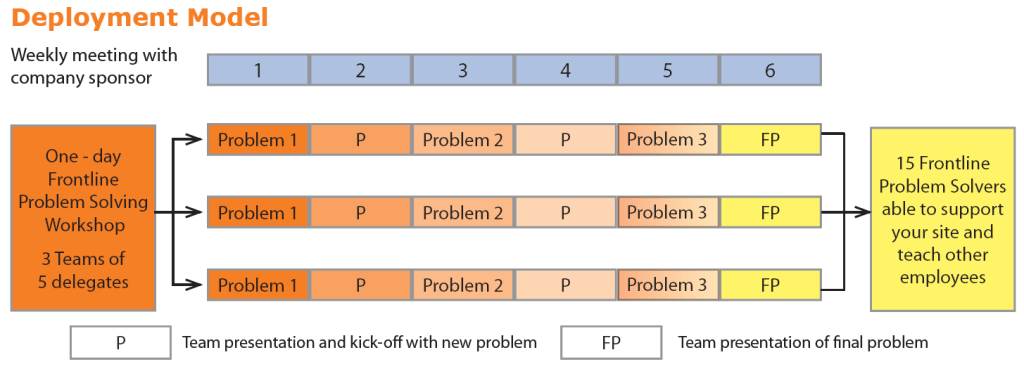

We have found an effective development process should contain a number of activities and involve people working in teams of 4 or 5 to accelerate their learning. A development process we have now used at numerous sites with great success involved establishing 3 teams of 5 people; then have the 3 teams complete a one-day workshop together to learn the 7 step process while each team works on recent problems or incidents from their workplace through steps 1-5. This is then complimented by 6 weekly 1-2 hour team meetings for each team to complete steps 6 and 7 of their first problem; then work through 2 more recent problems or incidents from their workplace. The outcome is the 3 teams will address 3 problems or incidents each, or 9 in total over the 7 week period which results in organisations reporting significant bottom-line gains as their people learn and apply Frontline Problem Solving in a team environment.

Example of Effective Development Process

Finding the Resources for Reactive Improvement

The challenge for most organisations is how best to allocate limited resources to the required amount of Reactive Improvement

An effective way to manage limited resources is to establish improvement policies that limit the amount of time allocated for Improvement. For example:

Frontline Problem Solving: The Problem or Incident needs to have caused an agreed impact on performance. For example, triggers are set, and when exceeded, a person will be allocated to take responsibility for the Frontline Problem Solving process and report back within an agreed number of working days with proposed Root Cause Solutions and an Action Plan for approval. Basically, the nominated person would play detective, visit the scene of the incident and question appropriate people etc. The typical policy for initially regulating the workload could be that a person can only be allocated 1 Frontline Problem at a time and that they have 3 working days to report back the proposed action plan. Obviously, once the action plan is agreed, then realistic target dates can be set for the completion and report back.

Note: The triggers would be progressively refined as fewer problems or incidents occur. For example, Toyota initiates a Frontline Problem Solving activity if they have a breakdown on their assembly line of ‘greater than 2 minutes’, whereas most organisations not advanced on their improvement journey may make their starting trigger as ‘greater than 2 hours’. They also allocate time each day for the people allocated to work on a Frontline Problem to have access to a competent facilitator who can assist them if required (e.g. at 1PM each day for half-an-hour the facilitator is available in a training room with whiteboard to assist with the process or documenting the outcomes on an A3 Summary Sheet).

Examples of Success

At a Food Processing Plant in NSW, Australia (which established 3 teams of 5 people to work through the 7 week Frontline Problem Solving Development Program and focus on recent problems on their production lines), a team solved a problem which saved the site over $110,000 annually, not to mention the savings from the other problems addressed by the 3 teams.

At a Winery in NSW, Australia (which established 3 teams of 5 people to work through the 7 week Frontline Problem Solving Development Program and focus on recent problems on their bottling lines), teams were able to identify a number of root causes:

- Labelling problem that caused $36,900 in losses;

- Falling bottles problem at the capper out-feed resulting in an 8% improvement in line efficiency;

- Glue leaking problem at the carton sealer saving 56 minutes per week in downtime; and

- Bottle crash problem on a line that was causing 42 hours downtime annually.

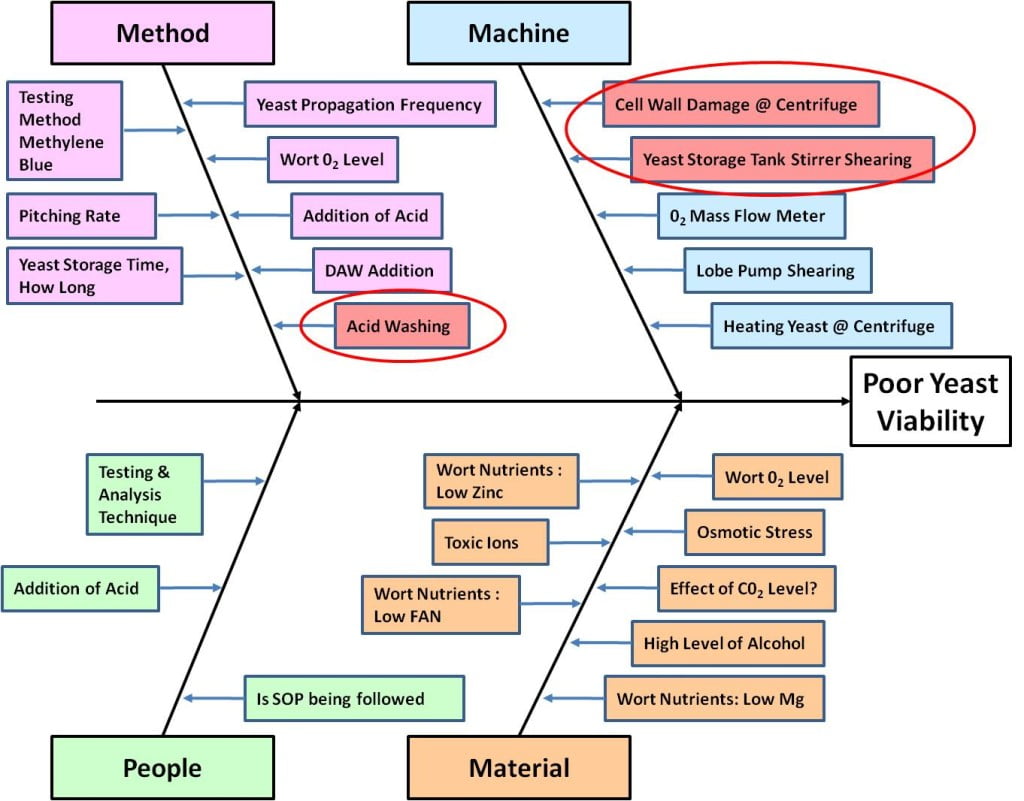

Following several incidents of brews being out of specification, a Brewery in Adelaide, South Australia initiated a Frontline Problem Solving team to address yeast viability.

Using the 7 Step Frontline Problem Solving process, the team focused their energy on getting to the root cause of the problem once and for all. After correctly defining the problem, the team then developed a Cause & Effect diagram as shown in Figure 1, to help identify all the possible causes resulting in poor yeast viability.

Figure 1 – Cause & Effect Diagram

Once numerous experiments were conducted and data was analysed both in house and by acknowledged experts, such as the group from Brewing Research International in the UK, the team was then able to identify the following three contributing causes to poor Yeast Viability:

- Yeast cell wall damage during centrifuging;

- Shearing caused by the Yeast Storage Stirrer; and

- Acid washing.

In the end the problem solving process not only identified the causes to the problem but also helped improve their knowledge of Yeast Viability and gain a better understanding of their Yeast Handling Process.

Key Learning

Unless the focus of your organisations improvement is the on-going development of your people, long term sustainability will become a significant issue.

The best way to create an environment for the on-going Frontline Problem Solving development of your people is to have them involved in Frontline Problem Solving at least 5% of their normal work time each week, and whenever you have events or incidents that impact on achieving your daily performance expectations.

By Ross Kennedy

Ross, who is based in Wollongong Australia, founded CTPM in 1996 after more than 20 years of manufacturing and operational experience covering maintenance, production, operations and executive roles along with 5 years of international consulting experience. Ross has been actively involved with Lean since 1985 and the application of TPM since 1990. In 1998 he developed and launched CTPM’s Australasian TPM & Lean methodology called TPM3. He is recognised as Australasia’s leading authority on TPM and TPM3. He is currently assisting sites throughout Australia, New Zealand, Indonesia and Thailand to strive for and achieve Operations Excellence.

Ross, who is based in Wollongong Australia, founded CTPM in 1996 after more than 20 years of manufacturing and operational experience covering maintenance, production, operations and executive roles along with 5 years of international consulting experience. Ross has been actively involved with Lean since 1985 and the application of TPM since 1990. In 1998 he developed and launched CTPM’s Australasian TPM & Lean methodology called TPM3. He is recognised as Australasia’s leading authority on TPM and TPM3. He is currently assisting sites throughout Australia, New Zealand, Indonesia and Thailand to strive for and achieve Operations Excellence.

For further information about Ross Kennedy visit www.ctpm.org.au or email: ross.kennedy@ctpm.org.au